Can art change the future?

In 19th-century Britain, many Victorians passionately believed art could change the future. As industrialisation swept through the country, bringing with it grinding poverty, overcrowded slums, and rising illness, artists began to look beyond beauty for beauty’s sake and instead, they asked: How can my work make a difference? For many, the answer was to create art that had a social purpose, something that could speak to the suffering, inspire reform, and perhaps even shape a better world.

Believing that art could change minds and spur action, artists produced paintings, prints, and decorative objects that were designed to not merely comment on social problems, but actively participate in solving them.

Found Drowned 1848–1850 George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village

The mid-19th century was a time of deep turmoil beneath the surface of Britain’s booming economy. While the Industrial Revolution brought immense wealth to a powerful few, it also left countless others in its shadow, struggling in overcrowded slums, choking on pollution, and scraping by in grinding poverty. Famine, financial crashes, and stark inequality became the backdrop to daily life for much of the population. People began to ask hard questions: How could a so-called “prosperous” nation allow such widespread suffering? Beneath the gleam of industry, the cracks were beginning to show, and many artists, writers, and reformers started to respond.

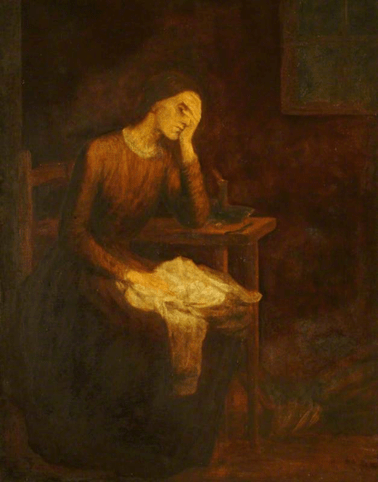

The Song of the Shirt 1902 Albert Daniel Rutherston (1881–1953) Bradford Museums and Galleries

As hardship deepened, so did the public’s appetite for change. Grassroots social movements began to rise, demanding justice and reform. Investigative journalism and official inquiries started pulling back the curtain on the dark realities of everyday life, dangerous factory conditions, abuse in workhouses, and filthy, overcrowded cities. For the first time, these issues weren’t hidden behind closed doors, they were being exposed, recorded, and broadcast to a shocked public. Britain’s social crisis was no longer invisible. It was in the newspapers, on the streets, and impossible to ignore.

Victorian artists played an important role in this process, and many artists believed that art’s purpose was to contribute to the general good and to improve life. They responded to the social concerns of their day by using their positions as public figures to write articles in political journals, donate their artworks to charity auctions, design banners or posters for social movements, or paint scenes that addressed the country’s most pressing problems.

Fig 1: Song of the Shirt 1850 George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village

In 1847, G. F. Watts painted Song of the Shirt, a haunting image that gave a human face to the silent suffering of seamstresses. His work captured a moment of national reckoning, as the brutal realities of the needle trades had just been exposed in a widely circulated labour report. The findings were shocking: women sewing for a living often worked up to three days without sleep, earning barely enough to survive. G. F. Watts’ painting didn’t just illustrate hardship, it amplified it, forcing viewers to confront the cost of the cheap clothing industry and the human toll behind every stitch.

G. F. Watts‘ painting makes the report’s conclusions vivid and human, capturing the exhaustion and despair of a seamstress working into the early hours. For the young G. F. Watts, painting was a charitable endeavour. As he wrote to a friend that year, he hoped to sell enough paintings so that he always had money to give to those living in poverty.

Victorian artists were at the frontline of reform efforts, using their art to develop strategies to confront the most urgent social problems of their day.

Many artists also hoped that their paintings would bring social issues into the view of audiences with the influence and financial means to take action. By exhibiting their work at fashionable exhibition venues, artists were guaranteed a large and influential audience. Paintings about contemporary social problems became increasingly popular, taking the place of the historical paintings, landscapes, and portraits that had previously dominated exhibitions.

By 1875, the critic John Ruskin wrote that so many social scenes were displayed at that year’s Royal Academy exhibition that the walls looked as though they were papered with issues of an illustrated newspaper.

Fig 2: Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward 1874 Sir Luke Fildes (1843–1927) Royal Holloway, University of London

Sir Luke Fildes was one of the artists whose work most reminded viewers of newspaper illustrations, and for good reason. Sir Luke Fildes began his career as a graphic artist, designing news illustrations of London street life. One of his best-known newspaper illustrations was the inspiration for his 1874 painting Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward, which shows people queuing for tickets to a London night shelter, known as a casual ward.

Fig 3: The Pinch of Poverty 1891 Thomas Benjamin Kennington (1856–1916) Foundling Museum

Sir Luke Fildes stoked his audience’s sympathy through realism, Thomas Kennington did it through idealisation. In his 1891 painting The Pinch of Poverty, a pretty little flower seller supports her mother and siblings by selling daffodils. Although the family is dressed in tattered clothes, showing that they have fallen on hard times, they are portrayed as attractively and sympathetically as possible to gain the viewer’s compassion.

In the scene, the flower seller appears to approach us, the painting’s viewers, to offer her wares, giving us the chance to buy a flower and relieve some of the family’s suffering. By appealing directly to its viewers, the work suggests that every one of us is responsible for coming to the aid of those who are less fortunate.

The First Public Drinking Fountain 1859–1860 W. A. Atkinson (active 1849–1870) Museum of the Home

In their effort to address a wide range of social issues, Victorian artists were just as concerned with pandemics and public health as we are today. By painting The First Public Drinking Fountain (1859), W. A. Atkinson issued a public service announcement to help quell London’s cholera epidemic. Cholera, spreads through diseased water, and caused millions of deaths in a series of pandemics during the nineteenth century.

This painting commemorated the opening of London’s first drinking fountain, which brought clean water to the residents of Holborn. By depicting members of all classes amicably using the fountain together, W. A. Atkinson‘s painting reminded viewers that the epidemic would only end if all Holborn’s residents shared the same clean water, and put hygiene and health above class differences.

Under the Dry Arch 1849–1850 George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village

Victorian artists were at the frontline of reform efforts, using their art to develop strategies to confront the most urgent social problems of their day. They hoped that their artworks would change minds, inspire discussion and debate, and shape public discourse in ways that could lead to broader social change.

#Art #Artists #NineteenthCentury #VictorianArtists

References:

Images:

Fig 1: Song of the Shirt

Fig 2: Applications for Admission to a Casual Ward

Fig 3: The Pinch of Poverty

Fig 4: The First Public Drinking Fountain

Websites:

Chloe Ward, Curator of ‘Art and Action: Making Change in Victorian Britain

Ward, C. (2020). Art for reform and social change in Victorian Britain. Art UK. [online] 18 Nov. Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/art-for-reform-and-social-change-in-victorian-britain.

[…] Song of the Shirt was inspired by a real-life exposé of a London seamstress, exposing the hidden suffering of women whose hands moved tirelessly behind the scenes of fashion and […]

LikeLike

[…] you’re navigating unpredictable health, limited energy, or a tight budget, this series is for you. For the days when a bag of barley and a handful of greens become a small triumph. For […]

LikeLike

[…] are textiles that tell stories not in words, but in pattern and Adire, a traditional indigo-dyed cloth from the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria — is one of those textiles. Its name […]

LikeLike