Original article by Lucy Brownson 27 FEBRUARY 2023

Updated: 23/7/25

I am always looking for interesting articles that can tell a person’s story through textiles. This story in particular, is very tragic, but it is interesting to understand the stories of women who want to protest their views and feelings through textiles.

Content note: This article refers to mental illness, including institutionalisation and ableist slurs.

“HER EMBROIDERIES ARE DEFIANT PROTESTS AGAINST A WORLD THAT DENIED HER A VOICE.”

I found onine an article Now Then, A magazine for Sheffield.

In 1837, Mary Frances Heaton of Doncaster confronted a vicar about an unpaid debt. Aged just 36, Mary Frances Heaton was charged with breaching the peace, and as a result, she was declared insane and committed to an asylum in Wakefield, where she remained for the rest of her life. Denied a voice, she stitched her story into cloth, using embroidery as a powerful form of expression and resistance.

Fig 1: Soprano Red Gray as Mary Frances Heaton. Stitched-Up-Theatre / Rosie Powell. A still from “The Unravelling Fantasia of Miss H.”—a contemporary opera blending physical theatre, radical stitching, and Mary’s embroidered protest samplers to tell her story in her own words. As featured in Lucy Brownson’s article “Subversive Textiles and Medical Misogyny in Yorkshire” on Now Then Magazine’s website.

Her so-called ‘crime? She challenged an Anglican vicar over the unpaid debt he owed her, decrying him in front of his parishioners as a ‘whited sepulchre, a thief, a villain, a liar and a hypocrite.’

Mary was born into a well-to-do Yorkshire family and built a respectable career as a music teacher, first in London and later in her hometown of Doncaster. It was there that she provided piano lessons to the daughter of Reverend John Sharpe, who failed to pay for her services. When Mary attempted to hold him accountable, she faced the same fate as many women of her time who dared to confront male authority — she was swiftly silenced and punished.

Having been detained overnight in Doncaster Gaol, Mary was deemed a ‘lunatic insane and dangerous idiot’ at trial the next day (she wasn’t allowed to testify, of course) she was sent immediately to Wakefield Pauper Lunatic Asylum for the next 41 years.

Amidst the inhumanity of her treatment and the torturous ‘remedies’ she was subjected to, Mary found a creative outlet through embroidery, producing samplers that capture something of the hardships she suffered at the hands of the church and state.

Her embroideries are defiant protests against a world that denied her a voice.

Thanks to the efforts of the Forgotten Women of Wakefield community history group, Mary’s story is now rightly held up as an example of medical misogyny as well as one of early art therapy, with a blue plaque unveiled to commemorate her.

Now, a theatrical portrayal of Mary’s life is en route to venues across South Yorkshire for the first time. Written and performed by Red Gray and Sarah Nicolls of Stitched-Up-Theatre, The Unravelling Fantasia of Miss H. blends contemporary opera, physical theatre and Mary’s stitched testimonies to tell her remarkable and tragic story in her own words.

Ahead of the show’s Doncaster date, Now Then sat down with soprano Red Gray to explore women’s history, mental illness, and the restorative power of community arts.

Hi Red! Thanks so much for talking with us. Before we get to Mary’s story and the production itself, could you tell us about your theatre company, Stitched-Up-Theatre? What drives and shapes your work?

Before establishing my own company, I was mainly part of other people’s theatre and opera projects. While they were immense fun, I wanted to be involved in more serious work with a social or political impact – to make a difference.

What came next was Stitched-Up-Theatre!

I was lucky enough to build an incredible team of women who were all extremely talented and happy to come on board for the project. The company’s mission is to tell stories that need to be told, by those who need to tell them, to those who need to hear them, through a convergence of physical theatre, opera and contemporary classical music.

The project quickly grew into something much more than opera and theatre, developing two other elements: radical stitching workshops for women’s community groups, and historical research together with the West Yorkshire Archive Service and Wakefield Mental Health Museum (where Mary’s samplers now live).

The Unravelling Fantasia tells the powerful story of Mary’s life, and the deplorable mistreatment she faced at the hands of the authorities. How did you first encounter Mary’s story? What compelled you to stage a production about her?

In 2016 I accepted (thank heavens) an invitation to go to a Wellcome Collection exhibition called Bedlam: The Asylum and Beyond, where I saw a little display about Mary’s story, two samplers and a short synopsis of what had happened to her.

I was struck by this – as a woman and a musician myself I could identify, and the fact that she had been shut away from the world for 41 years was just breathtaking.

It was as though her spirit was still alive in this story, and her words immortalised through the stitching that I did indeed feel compelled to research further.

I didn’t even know what I wanted to say at first: would it be a story about mental health history, about women’s rights, about social injustice? I just knew it needed to be told, and I could already imagine using music and the voice to dramatise it.

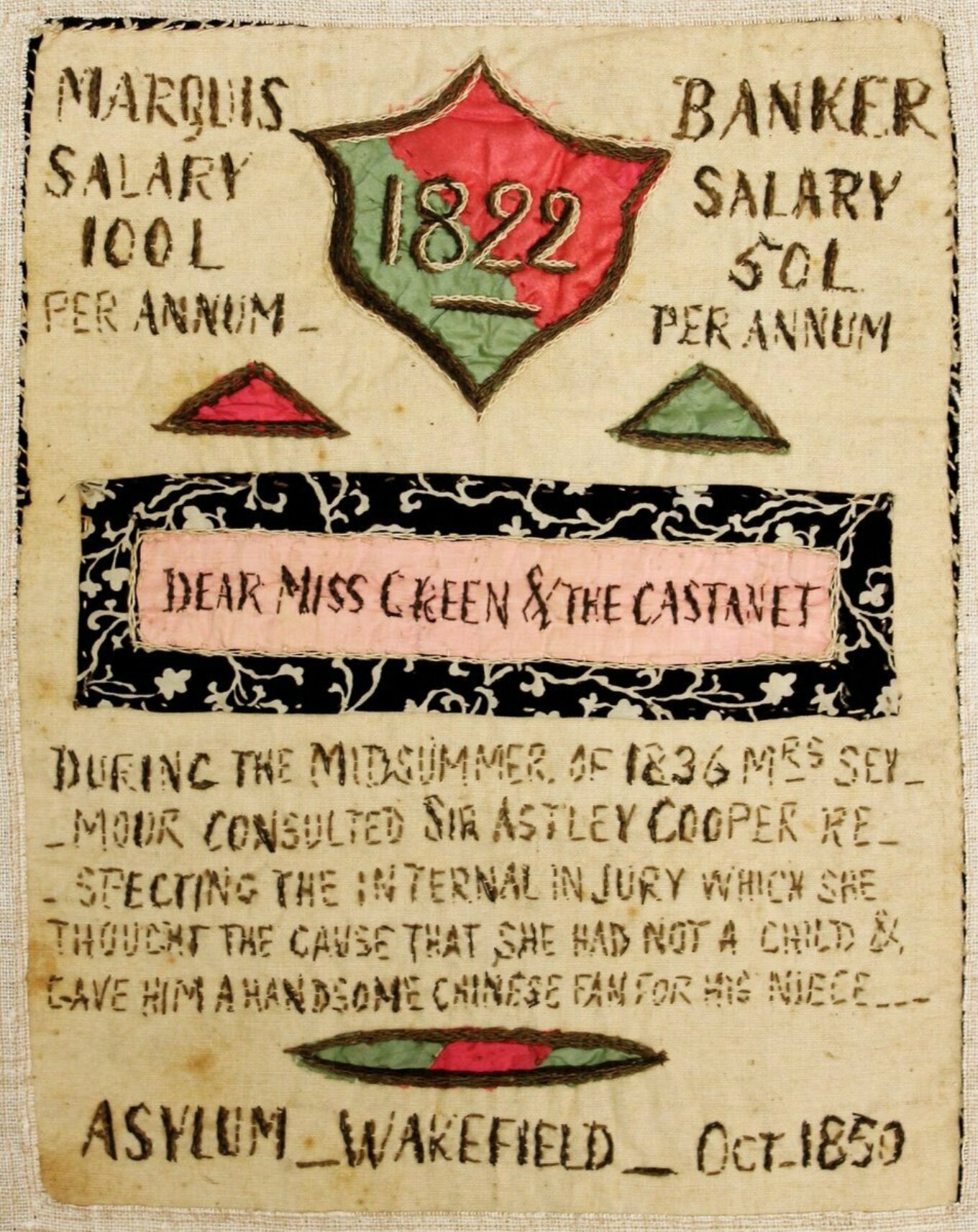

Fig 2: One of Mary Frances Heaton’s embroideries (c.1850), documenting an encounter between herself (‘Mrs Seymour’) and the British surgeon Sir Astley Cooper. Stitched in protest during her incarceration at Wakefield Pauper Lunatic Asylum, the sampler reflects Heaton’s defiant voice and detailed memory. Held in the collection of the Mental Health Museum, Wakefield. As featured in Lucy Brownson’s article “Subversive Textiles and Medical Misogyny in Yorkshire” on Now Then Magazine’s website.

For Mary, embroidery was a means of self-care and self-preservation. The research and development phase for this production has involved therapeutic embroidery workshops with women, and this is all part of a much longer lineage of women’s textile art as a means of resistance and self-expression. How do you see Mary’s stitching in relation to this history?

Initially, I was so in shock at Mary’s confinement that her embroidery almost seemed like a sub-plot… It took me a while to appreciate how resonant the survival of these samplers is.

It seems Mary was far ahead of her time in subverting the use of needlework as an instrument of oppression. It’s remarkable that the practice of embroidery – head lowered, eyes down to keep a woman in her place – is what Mary used to let us know in no uncertain terms what she felt about the patriarchal hierarchy.

I’m slowly becoming aware that this has been going on since women began to make. There’s a whole world of artistic and political discourse around women’s textile art, from the inspiring accounts of Lorina Bulwer and Agnes Richter, to conversations around women’s struggles for equity in the art world, to their gradual pivot towards the seemingly less threatening world of craft (which has nonetheless become a powerful mode of resistance).

The expressive embroidery workshops we held as part of the R&D phase enriched the show so much. I returned from a week of community engagement with my heart full of women’s stories, hopes, fears, dreams, their day-to-day struggles. They were brilliant, vulnerable and resilient women with stories to tell – the inner circle of bowed heads, counting our stitches, created a sanctuary where participants opened up to total strangers.

When I returned to writing I realised I wasn’t just telling Mary’s story, but the story of every woman whose voice has been silenced.

MARY WAS FAR AHEAD OF HER TIME IN SUBVERTING THE USE OF NEEDLEWORK AS AN INSTRUMENT OF OPPRESSION

You also held empowering singing workshops with women from the refugee and asylum-seeking communities of Leeds and Wakefield. What was your motivation there?

Many of the organisations in Yorkshire that we’ve partnered with for this project are Studios or Theatres of Sanctuary supporting communities of refugees and asylum seekers. We wanted to contribute to this important work to help some of the most vulnerable in the community, many of whom are women.

It felt fitting to extend the show’s message to these women, reaching out in friendship and support amidst the unbelievable challenges they faced. The LIFT YOUR VOICE workshops were funded by Opera North and they were held at Leeds Playhouse and Theatre Royal Wakefield earlier this year, attended by over 40 women.

There is power in music and lifting your voice with others, crossing that boundary of isolation, finding courage, and supporting each other through sound.

This bodily freedom can strengthen your mental and emotional wellbeing, offering a reminder that you’re part of something bigger than yourself. I wanted to offer hope and inspiration from Mary’s words and to keep our own and each other’s voices alive.

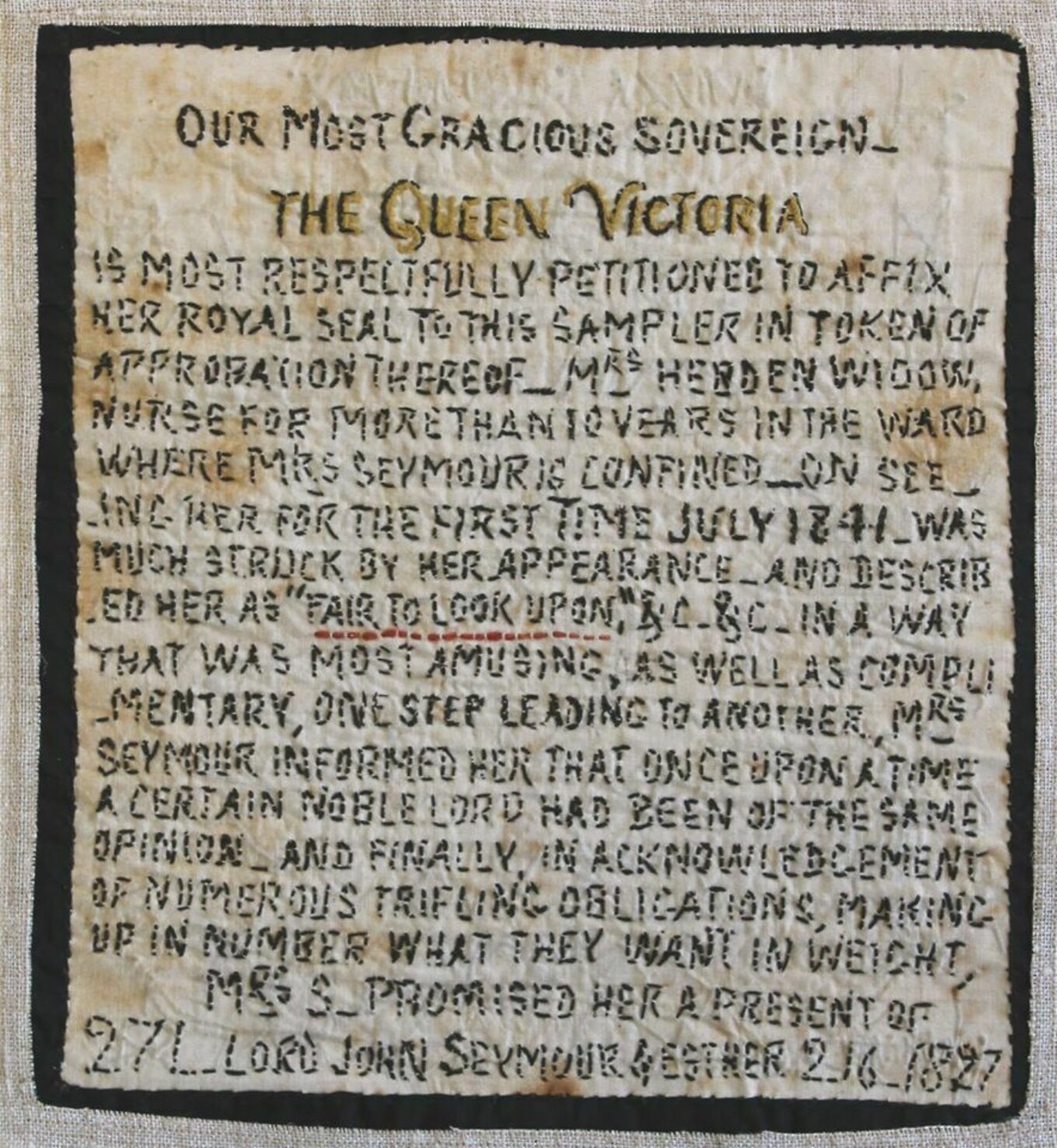

Fig 3: Mary Frances Heaton’s stitched petition to Queen Victoria (n.d.), alleging the circumstances of her incarceration. Created during her confinement at Wakefield Pauper Lunatic Asylum, the sampler documents Heaton’s protest against her treatment and the injustice she endured. A rare example of textile testimony addressed to the monarchy, it reflects her determination to be heard despite institutional silencing. Held in the collection of the Mental Health Museum, Wakefield. As featured in Lucy Brownson’s article “Subversive Textiles and Medical Misogyny in Yorkshire” on Now Then Magazine’s website.

The Unravelling Fantasia has been wildly popular so far. How does Mary Heaton’s story resonate with contemporary audiences?

There are so many areas of society wherein people currently feel let down, disempowered, and as though their voice isn’t being heard – you need only look at the huge differences between rich and poor and widespread lack of faith in the government.

Closer to home, we know so many women face emotional imprisonment through oppression, abuse, and intimidation, and further afield women are still risking their lives to speak out about their fundamental rights.

We often talk about how bad things used to be, but it doesn’t take much to see that there’s still so much suffering and cruelty.

I think that audiences empathise hugely with Mary and are astonished that she had the presence of mind to create such strong protestations in such a beautiful way. If you see the samplers, you’ll see the beautiful use of colour and composition as well as the metaphor and creativity used in each stitch. They’re extraordinary.

That she survived the ordeal of living in an asylum for 41 years was a human triumph, that she left us with a legacy that speaks to us about art, love, politics and human resilience is quite astonishing. She represents someone who fought to keep the flame of integrity alive in the face of extreme despair.

References:

Websites:

Now Then Sheffield (n.d.). “Subversive Textiles and Medical Misogyny in Yorkshire: The Unravelling Fantasia of Miss H.” [online] Available at: Now Then Magazine’s website [Accessed 21 Mar. 2023].