This article is based on a post written by the collections researcher at The Museum of English Rural Life Nicola Minney who has explored an unexpected historical ally in the suffrage movement: thesewing machine.

Lately, I’ve developed a deep interest in the sewing machine, a device I’ve been using personally, and one that has become a staple in both household and commercial settings in modern life. This remarkable piece of technology has a rich history that goes beyond its practical function; and has been a powerful tool for social transformation. The sewing machine played a critical role in empowering women, by turning a traditional “womanly” skill into a means of political and social influence. Giving women an avenue for financial independence and creative expression, the sewing machine became a symbol of self-sufficiency, helping many women advocate for their rights and rally for the vote. In a time when women’s roles were often confined to the domestic sphere, the sewing machine provided them with a unique opportunity to challenge societal norms and contribute in a meaningful way to movements for equality and change.

The Suffragette Sewing Machine: Crafting the Message of Change

For generations, it has been thought that sewing has been considered to be a marker for “chaste, domestic femininity,” and a way of demonstrating virtuous womanhood through skill and dedication to household tasks. Yet, at the height of the women’s suffrage movement, women strategically reframed the craft of sewing to voice their demands for enfranchisement. Sewing became a medium to voice strength, where the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and other organisations started crafting vibrant banners, sashes, and other symbolic items that would represent the women’s suffrage movement’s message. This became an important point in history for women, where change became possible.

The suffrage movement used colours in their textiles to convey powerful meanings: purple represented loyalty, white symbolised purity, and green stood for hope. These colours were deliberately chosen to reflect the movement’s vision for a brighter future and have since become iconic symbols of their cause.

In 1908, tens of thousands of women marched in London, wielding banners that were meticulously crafted by women for women from across the nation to symbolise their shared cause and these textiles, were produced by skilled hands, they illustrated unity and resolve, and elevated needlework from a domestic duty to a symbol of political strength.

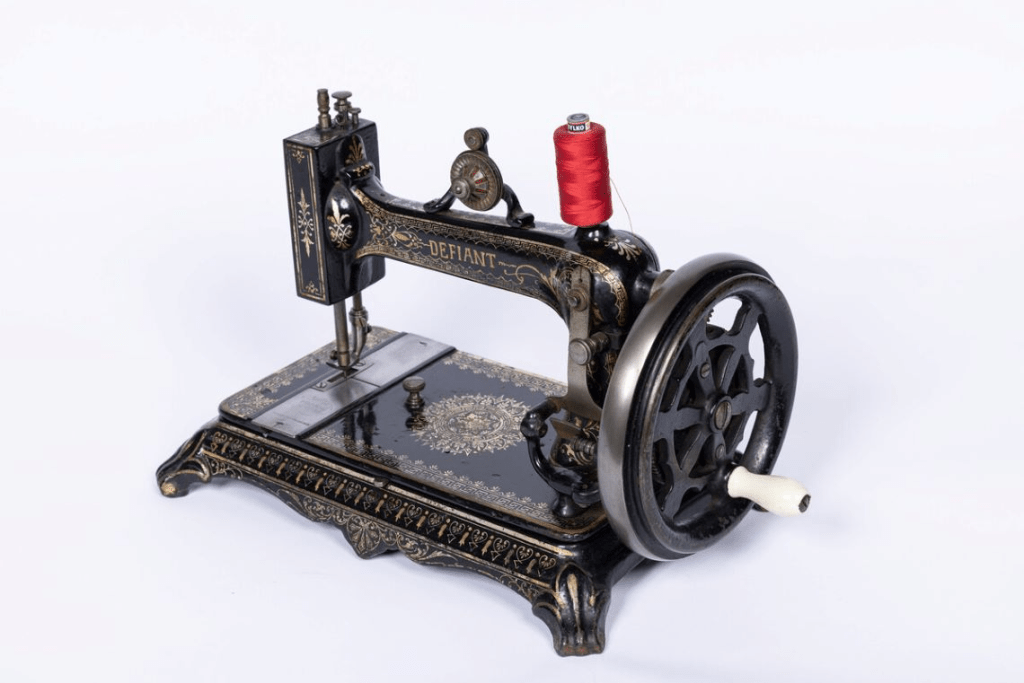

“The Defiant” Sewing Machine: A Tool of Empowerment

Fig 1: The original image source is not known. I found this image via The Museum of English Rural Life. The ‘Defiant’ was manufactured in Germany, but branded with the Harris name in England (MERL 81/91).

During the process of curating the “Sew What?” exhibition, (January 24, 2023-January 5, 2025) researchers discovered a significant sewing machine model that was known as “The Defiant,” this machine was manufactured by W.J. Harris & Co, along with another model called “Defiance.” These sewing machine models had links with the suffrage movement where the sewing machine and the bicycle allowed many middle and upper-class women to independently contribute to campaigns without needing male assistance or permission.

Fig 2: Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 Mary Lowndes c.1890s, platinum print by Arthur James Langton (1855–after 1919) Image taken found via Art Uk

Fig 3: A stained glass installation in St Martin and All Saints church, designed by Mary Lowndes in 1910 (Accessed via Openverse, credit Kotomi). Part of the collection at The Stained Glass Museum.

Mary Lowndes, a prominent artist and suffragette, played an instrumental role in the movement’s textile production. She trained as an artist, and leveraged her skills to craft banners, posters, and other campaign materials. Her involvement in the suffrage movement illustrated the importance of these creative skills in spreading awareness and rallying support for women’s rights.

Fig 4: The original source is not known. I found this image via the article found via The Museum of English Rural Life.

The Double Standard: Working-Class Women’s Role in the Movement

While the sewing machine offered newfound empowerment, working-class women faced significant challenges. The WSPU’s leadership often saw working-class women’s involvement as difficult and this was due to their demanding lives and a lack of education. Despite this, working-class women played a pivotal role in the suffrage movement, often creating banners and protest items from available fabrics rather than luxurious materials. Their contribution would highlight the vast socio-economic gaps in the movement and the sacrifices they made for the cause.

Fig 5: The original source is not known. A needlework sampler worked on open weave linen and embroidered with letters and numbers. It was made by the donor’s mother at Aldermaston School, Berkshire, in 1879-80 when she was 9 or 10 years old (MERL 90/56/3). This image was found via The Museum of English Rural Life.

Lady Constance Bulwer-Lytton, an upper-class suffragette, tried to expose these inequalities by disguising herself as “Jane Warton,” a working-class seamstress, during a protest in Newcastle. Upon being imprisoned under her alias, Lady Lytton faced the same harsh treatment as a working-class woman, including cold cells and force-feeding.

More details about Lady Lytton can be found here.

Fig 6:The ouriginal source of this image is unknown. I found it via The Museum of English Rural Life. Lady Lytton, 1908

She wrote about the brutal conditions for working-class suffragettes and what they had to endure in prison, revealing the harsh reality for many suffragettes.

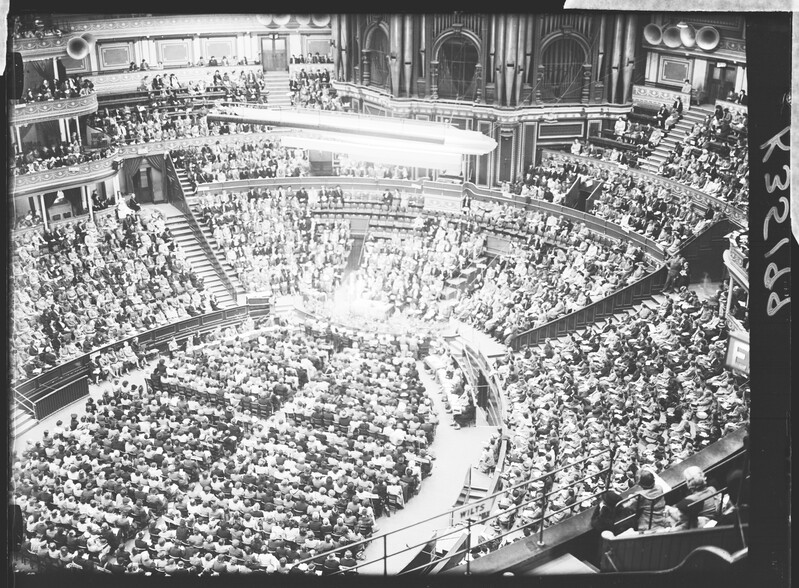

Fig 7: The original source of this image is unknown. National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies Meeting 13 June 1908 (Courtesy of Royal Albert Hall Archive) I found it via The Museum of English Rural Life.

Silent Protests: Needlework in Prison

Fig 8: Handkerchief embroidered by suffragette inmates at Holloway Prison, 1912. The Royal College of Physicians.

In prison, suffragettes were often forbidden from speaking to each other, and needlework became a method of silent resistance. Needlework was considered as an acceptable pastime for women, as it offered them a way to express solidarity and resistance in a silent way. In Holloway Prison, for example, sewing was a small activity but a meaningful form of communication, as some embroidered items survived, they would serve as a lasting tribute to and evidence for the suffragettes’ strength and resolve in the face of adversity.

The Sewing Machine’s Dual Legacy: Opportunity and Oppression

The sewing machine’s significance was two-fold. For some, it would bring financial independence, while for others, particularly in the context of the working-class it entrenched economic hardship. Factory owners often imposed steep markups on necessary tools like sewing needles and bobbins, they were deducted from workers’ already meager wages. The poor working conditions, alongside long hours and fines if their work was sub-standard, made the sewing machine a tool of exploitation for many women.

Fig 9: The original source of this image is unknown. Black and white photograph of King George V inspecting veterans at the Royal Show, Bristol. King George V was not sympathetic to the Suffrage movement. (MERL P FW PH2/R62/3) I found it via The Museum of English Rural Life.

The suffrage movement transformed the sewing machine into a symbol of independence and self-expression. Sewing allowed women, especially those in the lower social classes, to bring their issues to the forefront and amplify their voices. This complex duality made the sewing machine a particularly powerful symbol in the history of women’s rights.

Sewing a New Narrative: From Suffrage to the WI

Fig 10: The original source of this image is unknown. This spool is one of numerous sewing machine accessories that belonged to the donor’s mother, Marjorie Ellen Bunting, who was born in 1919 and received the machine for her 21st birthday. She used the machine and accessories in her work as a seamstress in a very small hosiery factory in Bulwell, Nottingham. (MERL 2011/76). I found it via The Museum of English Rural Life.

In 1915, former suffragettes helped to establish the Women’s Institute (WI) in England. This organisation offered women a platform to educate themselves, express opinions, and influence village life. The WI would provide a space where women, regardless of class, could come together, learn, and support one another. It became a forum for rural women to discuss public matters and assert their voices in a domain traditionally dominated by men. Many of the founding members had been involved in suffrage movements, bringing their advocacy experience to their communities.

Fig 11: The original source of this image is unknown. The Woman’s Land Army rally at the Essex Institute of Agriculture, Writtle, Chelmsford, Essex, marching past Lady Denman, D.B.E. founder of the National Federation of Women’s Institutes (MERL P FW PH2/W52/6). I found it via The Museum of English Rural Life.

The WI’s initiatives in the First World War would showcase how sewing and other traditional skills could serve a public need. They organised sewing drives, producing clothes and blankets for soldiers and refugees, and promoted food production to counteract wartime shortages. By the end of the war, their efforts had substantially increased Britain’s self-sufficiency, and the government recognised their invaluable contributions with financial grants.

Fig 12: The original source of this image is unknown. Meeting of the Women’s Institute at the Royal Albert Hall (MERL P FS PH11/K35199). I found it via The Museum of English Rural Life.

The Sewing Machine’s Enduring Symbolism

The sewing machine’s legacy is deeply embedded in the fight for women’s rights, from helping spread the suffragette message to fostering a new form of independence for women across the social spectrum. We can reflect on how this unassuming machine quietly empowered generations of women to stitch their way into history, piecing together a narrative that, although fraught with challenges, remains resilient and inspiring.

- You can learn more about the history of the sewing machine and it’s impact on women and children in the museum’s online exhibition Fast Fashion: Then and Now.

- Find out more about the collection of sewing machines, collected by James Barnett

Further Reading:

National Archives source material about Lady Lytton’s Autograph Letter Collection: Letters of Constance Lytton.

The Royal Albert Hall Archives Listing related to: Illustration of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) Meeting (Suffragists)

References:

Images:

Fig 1: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 2: Art Uk

Fig 3: The Stained Glass Museum

Fig 4: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 5: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 6: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 7: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 8: Royal College of Physicians

Fig 9: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 10: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 11: The Museum of English Rural Life

Fig 12: The Museum of English Rural Life

Websites:

Nicola Minney’s LinkedIn Profile: LinkedIn

Sources and Further Reading

i Wheeler, E. (2012) “The Political Stitch: Voicing Resistance in a Suffrage Textile” (Lincoln Textile Society of America University of Nebraska)

ii Sexton, S. (2018) “Subversive suffrage stiches” from The Quilter No. 154 Spring 2018

iii Sexton, S. (2018) “Subversive suffrage stiches” from The Quilter No. 154 Spring 2018

iv Sexton, S. (2018) “Subversive suffrage stiches” from The Quilter No. 154 Spring 2018

v Sexton, S. (2018) “Subversive suffrage stiches” from The Quilter No. 154 Spring 2018

vi The American Golfer, October 6, 1912

vii Jackson, S. (2018) “Women quite unknown’: working-class women in the suffrage movement” (British Library)

viii Jackson, S. (2018) “Women quite unknown’: working-class women in the suffrage movement” (British Library)

ix Lytton, Lady Constance (1914) Prisons & prisoners: Some personal experiences. By Lady Constance Lytton, aka Miss Jane Warton, 1869-1923 (London: William Heinemann)

x Wheeler, E. (2012) “The Political Stitch: Voicing Resistance in a Suffrage Textile” (Lincoln Textile Society of America University of Nebraska)

xi Thom, D. (2015) “A Stitch in Time: Home Sewing Before 1900” (The V&A)

xii Sherard, R.H. (1897) The White Slaves of England (London: James Bowden)

xiii Women Chainmakers (n.d.) ‘The Chain Trade Board’ (womenchainmakers.org.uk)

xiv Stainer, H. (2020) “Unfinished Business: Mary MacArthur” from Hazel Stainer Personal Blog

xv Stamper, A. (2007) “The WI and the Women’s Suffrage Movement” (The Women’s Institute)

xvi Stamper, A. (2007) “The WI and the Women’s Suffrage Movement” (The Women’s Institute)

xvii Stamper, A. (2007) “The WI and the Women’s Suffrage Movement” (The Women’s Institute)

xviii Squaducation (n.d) “The Founding of the Women’s Institute” (Squaducation.com)

xix McCall, C. (1943) Women’s Institutes William Collins : London]

xx Squaducation (n.d) “The Founding of the Women’s Institute” (Squaducation.com)

xxi Stamper, A. (2007) “The WI and the Women’s Suffrage Movement” (The Women’s Institute)

xxii Stamper, A. (2007) “The WI and the Women’s Suffrage Movement” (The Women’s Institute)

xxiii The Women’s Institute (2023) “About Us – History” (The Women’s Institute)