When we think of the Industrial Revolution in the North of England, cotton mills and towering chimneys often spring to mind. But behind the scenes, it was water—not just steam—that quietly powered progress. In this post, I’m exploring the fascinating history of Hyde Waterworks and how Manchester Corporation’s hydraulic power system transformed industry, infrastructure, and even urban legends.

Hyde Waterworks: A Town Transformed by Water

Hyde’s journey towards a reliable water supply began in 1831, when local figure Thomas Mottram secured an Act of Parliament to bring piped water to Hyde, Werneth, and Newton. This was a game-changer for public health and industrial growth.

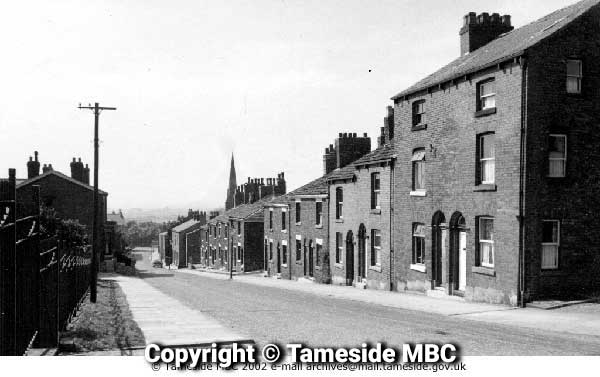

Joel Lane, Gee Cross – adjacent to the reservoir – looking down to Stockport Road at the bottom. The spire of Hyde Chapel

Over the years, reservoirs like Gee Cross (later Queen Adelaide), Stonepit, Diamond, and Arnold Hill were built to meet rising demand. When local water was deemed unfit for drinking in 1891, Hyde adapted. The Arnold Hill reservoir was Joel Lane, Gee Cross – adjacent to the reservoir – looking down to Stockport Road at the bottom. The spire of Hyde Chapetransformed into a hub for clean water from Manchester, complete with a pumping station built in 1893 to keep the town supplied.

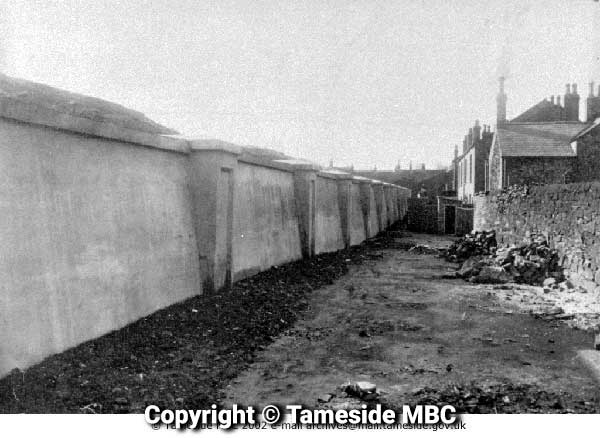

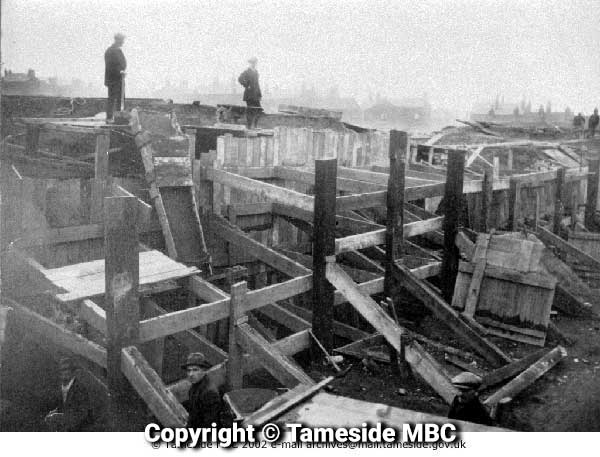

Building of Newton Reservoir

Miscellaneous, Construction, Waterways Lakes, Queen Adelaide Reservoir, Places E to H, Hyde, Gee Cross

By the late 1920s, most homes and businesses in Hyde had access to piped water—an incredible achievement at the time.

Manchester’s Hydraulic Power System: Innovation Ahead of Its Time

While Hyde was focused on drinking water, Manchester Corporation was busy with a different innovation—hydraulic power.

Launched in 1894, the Manchester Hydraulic Power System used high-pressure water to power everything from cranes and presses to lifts and looms. It was a cleaner, safer alternative to steam, especially valuable in the tight, busy urban spaces of the industrial city.

Key Pumping Stations:

- Water Street Pumping Station – Originally steam-powered, later converted to electric in the 1920s. Today, it’s part of the People’s History Museum.

- Liverpool Road Station – Joined the network in the 1920s, supplying power to Manchester’s bustling warehouses.

- Additional stations were added in 1899 and 1909 to meet rising industrial demand.

This system even powered the Manchester Town Hall clock, the organ at Manchester Cathedral, and the safety curtain at the Opera House. Yes—water was moving theatre curtains in the 1900s!

Water & The Textile Industry: A Perfect Match

Manchester’s identity as a textile powerhouse was closely tied to water—not just for dyeing fabric, but for running machinery.

- Cotton Baling: Hydraulic presses compressed cotton for easier storage and transport.

- Mill Machinery: Looms, carding machines, and dye vats all benefited from hydraulic pressure.

- Lifts and Cranes: Especially useful in commercial districts like Castlefield, where massive shipments moved in and out of warehouses daily.

Hydraulic power gave mills more control and cleaner operations than steam ever could—especially important in densely populated areas.

Folklore, Myths, and the Mechanical Spirits of the Mills

As with any great industrial leap, a bit of folklore sprang up along the way.

- Some workers believed hydraulic-powered looms were “alive”, due to their rhythmic, almost lifelike motion.

- There were tales of “mechanical ghosts“ in abandoned mills, where machines allegedly started on their own.

- Dyeing houses that used river water were sometimes said to follow rituals or superstitions around colour and season, giving rise to legends about “enchanted dyes.”

These stories, whether believed or not, are a beautiful reminder of how deeply technology was woven into everyday life.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

By the 1960s, Manchester’s hydraulic system began to decline due to corrosion and outdated equipment. It officially closed in 1972. Thankfully, part of this legacy lives on—the Water Street Pumping Station is preserved, and a full pump set can be seen at the Museum of Science and Industry.

As for Hyde, its reservoirs and waterworks laid the foundation for modern public services. They remind us that behind every industrial leap is a quiet infrastructure of pipes, pumps, and people.

Final Thoughts

Both Hyde’s waterworks and Manchester’s hydraulic power system are reminders of how engineering shaped not just factories, but communities. These systems brought clean water, enabled booming industries, and even inspired ghost stories along the way.

Let me know in the comments if you’ve ever visited the Water Street Pumping Station or have your own stories about the old mills and waterworks—I’d love to hear them!

References:

Websites:

Francis Frith Various Maps of Old Hyde

Museum of Science and Industry

National Library of Scotland – Map 1794 with references to Hyde Chapel and Hyde Hall