As you know (if you follow my blog) I’m deeply fascinated by the Industrial Revolution, especially the textile industry, not only because of its profound impact on Britain, but also due to a personal family connection that inspires me to learn more. This period of dramatic change reshaped both landscapes and lives, driving progress while demanding great sacrifices. In this article, I explore a lesser-known but revealing aspect of that era: the clothing worn by cotton mill workers. As they laboured to produce fabric for both domestic and global markets, their own clothing told a quieter story, one of hardship, resourcefulness, and resilience. From the high cost of a simple dress to the careful practices of mending and reusing garments, this post looks at what everyday clothing meant to those who kept the mills running, and how it mirrored the traditions of towns like Hyde.

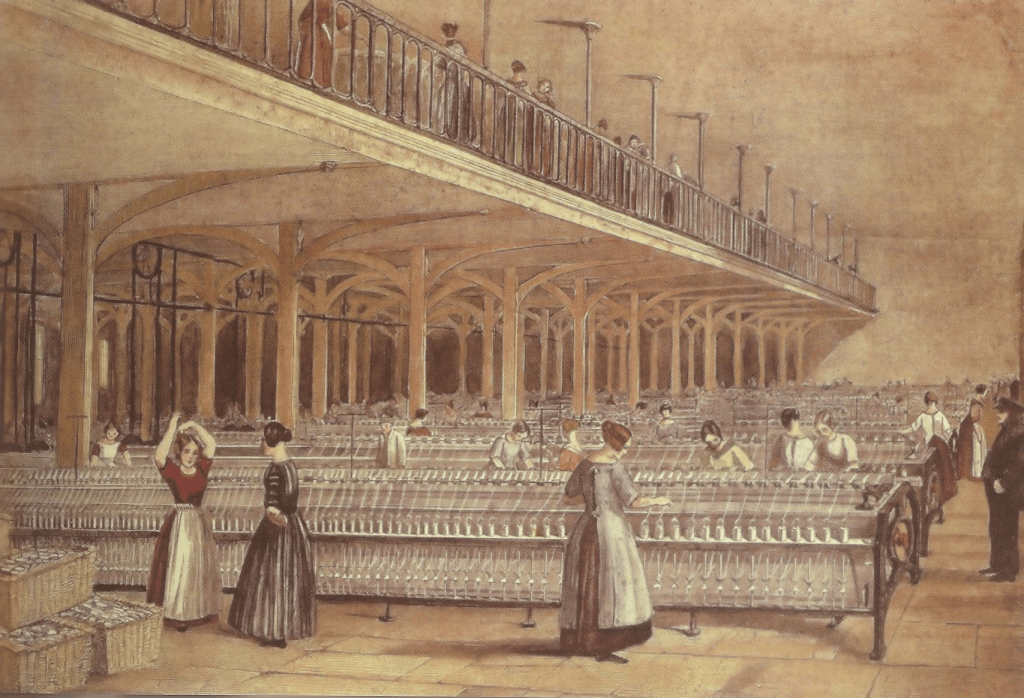

During the Industrial Revolution, the cotton mills of the United Kingdom, particularly in Northern England and towns like Hyde, Manchester, and Oldham, clattered with the relentless rattle of spinning frames and looms. Behind the machines were thousands of workers, many of them women and children, whose labour drove Britain’s booming textile industry. While the mills produced fabric in vast quantities, the irony is that the workers themselves often struggled to afford even basic items of clothing.

Wages vs. Wardrobe

Cotton mill workers in the 19th and early 20th centuries were typically paid low wages. For example, a female mule spinner in the 1850s might earn around 10 to 12 shillings per week, while younger “piecers” and child labourers earned even less, sometimes as low as 1 to 3 shillings. With such modest earnings, only a small fraction of their income could be spent on clothing after food, rent, and coal.

Clothing was a significant expense. A simple cotton dress could cost between 2 and 4 shillings, representing up to 40% of a week’s wage for a low-paid worker. Shoes were even more expensive, often costing a week’s wages or more. Coats, shawls, and outerwear were considered major purchases and were expected to last for many years.

Mending, Repairing, and Reusing

Given these constraints, working-class people made every effort to extend the life of their garments. Clothes were mended constantly, patches, darning, and hand-stitching were common. It was not unusual for garments to be handed down within families or re-purposed: old dresses might become aprons or children’s clothes, while worn-out shirts could be cut up for rags or quilting.

Mill workers were also known for purchasing second-hand clothing or “slop” clothing more about “slop” clothing here. Mass-produced garments were sold cheaply, often made from inferior materials, but the care taken to preserve what little they had was a testament to their resourcefulness and necessity.

Millwear vs. Traditional Dress in Hyde

The everyday clothing worn by workers in industrial towns like Hyde were simple, practical, and designed for functionality. Women often wore long skirts or dresses with aprons, while men wore rough trousers, shirts, and jackets. On workdays, clothing was often dark-coloured and made from sturdy cotton or wool blends. Protective garments, such as shawls or pinafores, were commonly used to shield clothes from dust and oil in the mills.

During Sundays or holidays, workers took pride in donning their “best” clothes, they were often carefully preserved items that reflected more traditional styles or local preferences. In places like Hyde, older forms of rural or regional dress had begun to fade by the late 19th century, but echoes remained: women might wear bonnets or shawls in traditional styles, while men might retain specific cuts of jackets or hats associated with local heritage.

These occasions highlighted a stark contrast between the drab, functional clothing of mill work and the more decorative, albeit modest, attire associated with community events, chapel services, or market days.

Conclusion

Although they laboured in the heart of Britain’s textile industry, cotton mill workers faced ongoing challenges in clothing themselves. Their wardrobes were shaped not by abundance but by frugality, skill in repair, and a culture of reuse. In towns like Hyde, the evolution from traditional dress to industrial practicality tells a broader story of social change, of how working-class identity was stitched together, one patch at a time.

References:

Image:

Websites: