The Ashton family has already been a significant focus of my previous writings, however I do believe it is crucial to look further and contextualise their role in the development of Gee Cross and Hyde, as well as their contribution to the textile industry. The Ashtons were instrumental in shaping the economic and industrial landscape of this area.

In my ongoing research into the history of the Ashton family and their influence on Gee Cross and Hyde, I came across a collection of fascinating images that offers further insights into the area’s past. These visuals are not only of interest to those studying the Ashton family’s legacy but also to anyone with a passion for local history. They help to illustrate the transformation of Gee Cross and Hyde and beyond over time and provide valuable context for understanding the social and industrial developments that shaped the community and more broadly the family’s influence in British history. For local history enthusiasts, these images offer a tangible connection to the people and places that played a pivotal role in the region’s growth.

Fig 1: The image titled “Gerrards, from an old postcard” appears in a detailed post on the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog, which explores the Ashton family’s history in Hyde. Gerrards was the name of the Ashton family farm at Gee Cross, which evolved into a substantial house by the late 17th century. It was eventually demolished between 1998 and 2001 and replaced by townhouses.

I recently came across a fascinating article that explores the history of the Ashton family, which tracks where different members of the family eventually settled. My original research focused on uncovering more about Gerrards—the family farm at Gee Cross, which by the late 17th century had come to be known by that name. Over time, a substantial house developed from the original farm buildings. It is well-documented that Gerrards was home to the Ashton family, and that Samuel Ashton and his brothers played a significant role in establishing a mill on the site. The house remained standing until relatively recently but was demolished sometime between 1998 and 2001 to make way for a row of three-storey townhouses.

The Ashton family, who rose to prominence in the 16th century as yeoman farmers in Hyde, Stockport, are a compelling part of south-east Lancashire’s local history. The Ashton family’s roots stretch back even further, with connections to two earlier branches of the Ashton name. The Hyde Ashtons are believed to be descended from a line based in Stoney Middleton, Derbyshire—an area known for its limestone quarries and natural beauty—and an even older lineage originating in Ashton-under-Lyne, a historically significant settlement long before it became associated with the Industrial Revolution. These ancestral links not only ground the family firmly in the region’s history but also reflect the broader migration and establishment of the Ashton name across both industrial and rural landscapes. While the Hyde branch is well documented, these wider connections reveal a richer and more intricate family history.

The Ashton Family’s Origins

The proximity of Hyde and Ashton-under-Lyne makes it plausible that the Hyde Ashtons could have a more direct connection to this Lancashire branch than previously thought. Both towns are located in the south-east of the county, and Ashton remained a common surname in the region. It is questionable as to whether the Hyde Ashtons came directly from Ashton-under-Lyne or via Stoney Middleton, what does remain clear is that by the 16th century, they were well-established in Hyde, where they laid the foundations for future success.

he Role of Yeoman Farmers in Local Society

As yeoman farmers, the Ashton family belonged to a respected and relatively prosperous class in early modern England. Positioned socially between the gentry and tenant farmers, yeomen were often regarded as the backbone of rural society. They typically owned or leased the land they worked, managing it themselves, with holdings substantial enough to provide a comfortable living. In Hyde, the Ashtons would have played a key role in the local agricultural economy—contributing to food production while also earning social standing through their land ownership and self-sufficiency.

This role as yeoman farmers also gave the family a degree of social mobility, this allowed them to rise above subsistence farming and potentially invest in other ventures. This status would become important in later generations when the Ashton family transitioned from agriculture to industrial enterprises, most notably in the textile industry.

The Industrial Transformation of Hyde

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Industrial Revolution was reshaping the British economy, and the Ashton family emerged as influential players in Hyde’s transformation. Like many landowning families of the time, they seized the opportunities brought by the rapid expansion of textile manufacturing—a sector that soon became the backbone of the region’s economy. With the rise of cotton mills across Hyde and neighbouring towns, fuelled by technological innovation and access to raw materials, the Ashtons positioned themselves at the forefront of this industrial boom, becoming prominent figures in the area’s evolving commercial landscape.

Samuel Ashton and his brothers were instrumental in transforming Gerrards—not only their family residence but also a focal point of industrial enterprise—into a hub of textile production. Their establishment of mills on the site played a key role in positioning Hyde as a significant centre for the cotton industry, contributing to Lancashire’s emergence as a global powerhouse in textile manufacturing. This marked a notable evolution from the family’s earlier roots as yeoman farmers, reflecting both their adaptability and entrepreneurial vision during a time of rapid economic and technological change.

Legacy of the Ashtons in Hyde and Beyond

The Ashton family’s legacy is deeply woven into the history of Hyde and the surrounding region, and this is because their early role as yeoman farmers established them as prominent figures in the local community, while their later ventures in the textile industry solidified their place as industrial pioneers. As Hyde grew and transformed during the Industrial Revolution, the Ashtons were at the forefront, contributing not only to the economic development of the area but also to its social and cultural identity.

The wider connections of the Ashton family—to Stoney Middleton, Ashton-under-Lyne, and potentially other branches across the country—highlights the mobility and interwoven nature of family networks during a time of profound change in Britain. These links suggest that the Ashtons were not confined to their immediate locality, but were part of a broader tapestry of families influencing the economic and social development of the region.

In summary, the Ashton family’s journey from 16th-century yeoman farmers to industrial leaders in the 19th century mirrors the broader transformations that occurred in Britain during this period and their story offers valuable insights into how local families adapted to and drove the changes that redefined the British countryside, industry, and society as a whole. The Ashton name, long associated with south-east Lancashire, continues to evoke a rich history of resilience, innovation, and community in the face of a rapidly evolving world.

THE ASHTON FAMILY’S RISE TO GENTRY THROUGH THE COTTON TRADE

The Ashton family’s rise to gentry status in the 18th century marked a turning point in their social and economic trajectory. Originally yeoman farmers in Hyde, Stockport—then a rural area centred around Hyde Hall along the River Tame—the family capitalised on the expanding cotton trade to diversify their interests and cement their local influence. At the time, what would later become Hyde town centre was little more than a small cluster of houses known as Red Pump Street. Although Hyde functioned as its own township, it historically fell within the parish of Stockport until the Industrial Revolution spurred its transformation into a distinct town. The story of Benjamin Ashton (1718–1791) exemplifies this shift. Among the first in the family to transition from agriculture to textile production, his work in weaving cotton and linen cloth laid the groundwork for the Ashton family’s emergence as significant industrialists and helped propel them into the ranks of the gentry.

The Emergence of the Cotton Trade in Hyde

During the mid-18th century, the British cotton trade was still in its very early stages of development. Although cotton had been imported into Britain since the 17th century, it wasn’t until technological advances in spinning and weaving during the 1700s that the industry began to flourish. During this time, cotton cloth was typically woven with a combination of materials. Linen warps were stronger than cotton and came from the North of Ireland, while the cotton weft was spun in Lancashire, the heartland of the emerging cotton industry.

Benjamin Ashton, recognising the potential of this new industry, seized the opportunity to engage in cotton weaving, setting the stage for his family’s eventual rise. The process Benjamin Ashton used involved having local handloom weavers in the Hyde area weave cloth from the cotton weft, while linen warps were still commonly used for added strength. This early phase of the industry required a great deal of manual labour, with weavers working at home on handlooms, a system that persisted until the introduction of mechanised factories later in the century.

benjamin Ashton’s Role in the Textile Trade

Benjamin Ashton’s entry into the cotton trade was a significant turning point for the family. Although he began as a farmer, Benjamin Ashton expanded his operations by coordinating local handloom weavers to produce cotton cloth. He acted as a middleman, by organising the production of fabric in Hyde and then taking the finished goods to Manchester, which had become a burgeoning hub for cotton trading, to sell. At the time, Manchester was rapidly establishing itself as the centre of the cotton industry, with its warehouses and markets attracting merchants and buyers from across Britain.

As Benjamin Ashton engaged in this trade, he was at the forefront of a key transformation in British industry. His efforts to produce and sell cotton cloth were part of the broader shift from a rural, agrarian economy to an industrial one that was driven by textile production. The wealth he accumulated from this trade allowed him to elevate his family’s status, by positioning them as part of the emerging gentry class in Hyde.

From Yeoman Farmers to the Gentry

The shift from farming to industrial entrepreneurship allowed the Ashton family to amass wealth and influence in the local community. As in earlier generations, the Ashtons had been prosperous yeoman farmers, owning or leasing land and maintaining a comfortable standard of living through agriculture the opportunities provided by the cotton industry far exceeded what farming alone could offer. By diversifying into textile production and trade, Benjamin Ashton moved his family into a new social class—one that would be defined by the wealth that was generated through industry rather than the land.

It can be seen that the timing of Benjamin Ashton’s involvement in the cotton trade was crucial as the industry was expanding rapidly, and early investors in the production and sale of cotton goods found themselves in advantageous positions as demand for textiles grew both domestically and internationally. When mechanisation began to take hold in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, those who had already established a foothold in the industry—like the Ashtons—were able to build on their early successes, further increasing their wealth and influence.

The Ashton Legacy in Hyde and Beyond

Benjamin Ashton’s legacy and his ventures into the cotton trade can still be seen in the history of Hyde and the surrounding areas. The success of Benjamin Ashton not only elevated the Ashton family but also contributed to the industrial development of the region as more families like the Ashtons transitioned from farming to industry, the landscape of south-east Lancashire changed dramatically, seeing more factories and mills, with a growing population of industrial workers reshaping the economy and society.

The Ashton family’s transition into gentry status was built on the foundation of Benjamin Ashton’s engagement with the cotton industry and also he had a lasting impact on the town of Hyde. The family became important figures in the local community, with later generations establishing mills and contributing to the region’s growing industrial infrastructure. The Ashton family’s investments helped transform Hyde into a significant centre for textile production and played a key role in the broader Industrial Revolution that reshaped Britain.

Today, the Ashton name is associated with both the agricultural roots of Hyde and its industrial expansion, embodying the transition from traditional land-based wealth to the new economic order that was driven by manufacturing. Benjamin Ashton’s legacy serves as a reminder of how entrepreneurial spirit and adaptability can lead to lasting social and economic change, both for a family and for the communities they helped to build.

Samuel Ashton (1742-1812) continued this business, and six of his seven sons went into partnership in a larger-scale factory-based cotton-spinning business, with mills at Gerrards Wood and Wilson Brook in Godley. Their mills were soon steam-powered and the Ashton family bought their own coal mines to secure their supplies. They also established a calico printing works at Newton Bank. In 1823 the brothers agreed to separate their businesses, with the two eldest, Samuel and Thomas, taking the major shares. Samuel established himself at Apethorn Mill and soon afterwards built Woodley Mill, while Thomas ran the factory at the Hollow. John’s business interests seem to have shifted to Manchester, while James was at Newton Bank. The brothers all became rich on the proceeds of the cotton trade, and were able to purchase or build gentlemen’s houses; it’s sobering to compare the fortunes they left at death with those of contemporary but longer-established gentry families.

Benjamin, Robert and Joseph were childless, and John left an illegitimate daughter. After providing for her, and making generous legacies to his surviving siblings, he left the bulk of his estate to the Government and towards paying off the national debt, a quixotic gesture which took some £200,000 out of the family (some £263m today).

Samuel, Thomas and James had descendants to inherit their businesses and seats. Samuel Ashton (1773-1849), who as the eldest son inherited Gerrards, and built Pole Bank Hall at Hyde in about 1820. His eldest son, Thomas, having been murdered in 1831 by agitators who were trying to intimidate the local millowners, Pole Bank and his businesses were left to his third son, Benjamin Ashton (1813-89), who remained unmarried and bequeathed them to his nephews, Frederick and Godfrey Burchardt, who sold the house.

James Ashton (1777–1841) built Newton Lodge in Hyde around 1820 and, by 1835—perhaps envisioning a quieter life in the countryside—purchased Little Onn Hall in Staffordshire. These estates passed to his only son, John Ashton (1800–1844), who died young, and then to his grandson, Charles James Ashton (1830–1891). Upon coming of age in the 1850s, Charles rebuilt Little Onn Hall, marking a distinct shift away from the family’s industrial and urban origins towards a more landed, rural identity.

After Charles’ widow died in 1893, Little Onn and Newton Lodge were inherited by their teenage daughters, Eveline and Amy Ashton. Remarkably, before marrying in 1902 and 1903, the sisters undertook the ambitious project of extending Little Onn Hall and commissioning renowned landscape designer Thomas Mawson to create an elegant garden. Their vision and initiative at such a young age would raise fascinating questions about their motivations and influence. In a lasting gesture to their hometown, the sisters also donated Newton Lodge to the people of Hyde, transforming it into a public park.

Fig 2: Ford Bank, Didsbury, originally built in 1854 for Thomas Ashton (1818–98), appears in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog. Thomas Ashton, a prominent cotton manufacturer and philanthropist, commissioned the house from architect Edward Walters. Ford Bank later became known for its impressive art collection and its role in Manchester’s civic life. Image from Manchester Library.

Thomas Ashton (1775-1845) is remembered as the most philanthropic of the Ashton brothers, whose efforts went beyond running successful mills, by extending to the well-being of his workers and their families. He built housing and a library for his employees, that would ensure that they had access to education and comfortable living conditions. Thomas Ashton understood the importance of education, he also constructed a school for the children of his workers, laying the groundwork for social reform and worker welfare within the local community and this commitment to bettering the lives of his employees reflected not just his entrepreneurial spirit but also his progressive Unitarian beliefs, a religious philosophy that emphasised social justice and compassion.

This tradition of philanthropy didn’t end with Thomas Ashton it was carried forward by his son, also named Thomas Ashton (1818-1898), who became an equally important figure both in the business and social fabric of Hyde. Under his management, the family’s industrial ventures would flourish, with Thomas Ashton eventually owning three factories and employing nearly 3,000 people by the time of his death. His efforts to support his workforce were particularly notable during the cotton trade depression of 1861-1865, which was caused by the American Civil War. While most mills were forced to close or drastically reduce their operations, Thomas Ashton kept his mills running at a financial loss, ensuring that his employees remained employed during these difficult times.

Thomas Ashton’s dedication to the welfare of others would be extended beyond his workforce. He supported a range of charitable causes playing an active role in the development of educational institutions. His contribution to the Unitarian community in Hyde was marked by the construction of a new chapel at Flowery Fields, which he strategically located near one of his mills, and would serve both the spiritual needs of his workers and the local population. Ashton’s charitable work and commitment to his workers earned him widespread respect, and when Hyde became a borough in 1881, he was appointed as the town’s first Mayor—a testament to his popularity and influence.

Beyond his contributions in Hyde, Thomas Ashton’s influence would spread across Cheshire and Lancashire, where he became involved in local politics. His standing in society was such that he was invited to stand for Parliament and was offered a baronetcy, both of which he declined, preferring to focus on his community and business interests. In 1854, Thomas Ashton commissioned the renowned architect Edward Walters to design a new residence, Ford Bank, in Didsbury, Lancashire. (In 1854. Didsbury was part of Lancashire which was historically a township within the parish of Manchester, which was located in the Salford Hundred). Didsbury remained in Lancashire until 1904, when it was incorporated into Manchester as the city expanded. Before urbanisation, it was largely rural, with records of it existing as a small hamlet as early as the 13th century. This grand home became a reflection of his success and a place where he amassed an impressive art collection, further highlighting his cultural and intellectual interests.

Ashton’s philanthropic legacy continued through his family, and most notably through his unmarried daughter, Margaret Ashton (1856-1937), who pursued a career in politics and social reform after her father’s death. Margaret’s initial activism was centred around the Liberal Party, but eventually, she parted ways with the party over an issue of women’s suffrage, which aligned herself with the Labour Party to advocate for women’s rights. Her later years were dedicated to campaigning for pacifism and furthering the cause of gender equality, making her a significant figure in both local and national political movements.

The Ashton family’s story is one of industrial success intertwined with a deep sense of social responsibility. Through the actions of Thomas Ashton and his descendants, they not only helped shape the industrial landscape of Hyde but also left a lasting legacy of philanthropy and social reform that extended well beyond their business ventures.

Fig 3: The image of Vinehall, Robertsbridge, Sussex, as extended for the 1st Baron Ashton of Hyde, appears in the LLanded Families of Britain and Ireland blog. The house was originally a mid-19th-century Italianate residence, later enlarged by Thomas Gair Ashton after he purchased it in 1902. It remained in the family until the death of his widow in 1938, after which it became Vinehall School

THOMAS GAIR ASHTON: FROM POLITICS TO PEERAGE

Thomas Gair Ashton (1855-1933), the eldest son of the philanthropic industrialist Thomas Ashton (1818-1898), chose to build a career in politics rather than follow directly in his father’s footsteps in the family business. His life marked a shift from the traditional focus on industry that had defined the Ashton family for generations, to a more public-facing role in political and civic affairs. As the first in his family to receive the classical public-school-and-Oxbridge education typical of the English upper class, Thomas Gair Ashton represented a new chapter for the Ashtons, blending the legacy of industrial success with public service and political ambition.

A New Kind of Ashton Education

Unlike his father, who had attended a nonconformist academy and a German university, Thomas Gair Ashton benefited from an education that aligned him with the British elite. He was the first in his family to attend both a traditional British public school and then Oxford University, which positioned him for a life of political involvement and influence. This education not only reflected the family’s growing wealth and status but also opened doors for Thomas Gair Ashton in the world of British politics, where connections and pedigree played a crucial role.

Early Political Career

Thomas Gair Ashton’s first foray into politics came in 1885 when he was elected as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Hyde, the same town where his family’s mills had helped shape the local economy. His time as MP for Hyde was brief and lasted only until 1886 when he lost the seat. He was undeterred, and continued to pursue a political career, by contesting the Hyde seat again in 1886 and 1892, although he was unsuccessful in both attempts.

In 1895, Thomas Gair Ashton was elected as the MP for Luton, marking the beginning of a longer, and more stable period in his political life. He represented Luton in Parliament until 1911 and played a significant role in Liberal Party politics during a time of great social and economic change in Britain. Ashton’s political career would span the era of significant Liberal reforms aiming to address issues of poverty, social welfare, and workers’ rights, many of which would have directly impacted communities like Hyde that had been built on industrial labour.

Baron Ashton of Hyde

When Thomas Gair Ashton retired from Parliament in 1911, his service and contributions to public life were recognised by creating the peerage title 1st Baron Ashton of Hyde. This elevation to the peerage reflected Ashton’s status as both a respected politician and a member of one of Britain’s leading industrial families. The title linked him explicitly to Hyde, which honoured the town that had been central to his family’s legacy and his own early political career.

Vinehall: A New Home and Legacy

In 1902, during his political career, Thomas Gair Ashton purchased a mid-19th-century Italianate house called Vinehall in Robertsbridge, East Sussex. The house became his family’s country estate, and Ashton made significant expansions to the property, by turning it into a grand residence suitable for a man of his growing stature. Vinehall, with its classical architecture and enlarged grounds, would symbolise Ashton’s entry into the ranks of the British gentry, further distancing him from the industrial origins of his family.

Vinehall remained in the Ashton family until the death of his widow in 1938. After her death, it was sold later becoming a preparatory school. This transformation from a private residence to an educational institution mirrored Ashton’s own commitment to public service, with the estate continuing to serve a broader social purpose even after it left the family’s hands.

The Family Business and Its Legacy

As Thomas Gair Ashton pursued his political career, the management of the family’s cotton business shifted into the hands of professional managers and this transition would mark the end of direct Ashton family involvement in the mills and the textile industry that had been the foundation of their wealth and influence in the beginning. The business continued to operate successfully for many years before eventually being bought out by Courtaulds in 1968, a major British manufacturer of textiles.

Although the Ashtons had long since moved away from the day-to-day operations of the mills, the family’s industrial legacy remained and was tied to Hyde, where their contributions to the textile industry had played a key role in the town’s development. Preferring to focus on politics and public life, Thomas Gair Ashton shifted the family’s influence from industry to the broader sphere of British governance and public affairs.

Margaret Ashton and a New Political Legacy

Though Thomas Gair Ashton’s career centred mainly on traditional liberal politics, his sister Margaret Ashton followed a more radical path. She was a committed suffragist and advocate for women’s rights, and she became a prominent political and social reformer in her own right. Her activism for pacifism, women’s suffrage, and social justice in the early 20th century highlighted the progressive spirit that had long been part of the Ashton family ethos.

In sum, Thomas Gair Ashton’s life reflected the broader changes in British society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While his family’s roots were firmly planted in industry, his career in politics and public service represented a new phase in the Ashton family’s legacy and one that bridged the worlds of industrial entrepreneurship and political leadership. His contributions to both Hyde and the national stage left a lasting impact on the community and on the political landscape of the time.

When Thomas Gair Ashton, who was the 1st Baron Ashton of Hyde, passed away in 1933, his title and responsibilities passed on to his only surviving son, Thomas Henry Raymond Ashton (1901-1983), who became the 2nd Baron Ashton of Hyde. Unlike his father and grandfather, having strong ties to the industrial heartlands of south-east Lancashire and north-east Cheshire due to the family’s deep involvement in the cotton trade, the 2nd Baron Ashton of Hyde would have a different focus and passion. Having been raised in Sussex, his connection to the industrial towns that had been central to his family’s legacy was distant. Instead, his interests lay in the rural, aristocratic tradition of hunting.

In 1929, Thomas Henry Ashton purchased Broadwell Hill, which was a Victorian house in Gloucestershire, and was situated in prime hunting territory. The house, Although relatively modest by aristocratic standards, the house was ideally located for his pursuits, particularly fox hunting, which became a central part of his life. Around ten years later, during the late 1930s, he enlarged the house with the help of architect Eric Cole from Cirencester, transforming it into a more substantial country residence that befitted his role as a prominent figure in the hunting world.

Broadwell Hill was ideally positioned within the territory of the Heythrop Hunt, one of the most prestigious fox hunting packs in England, whose hunting grounds spanned the Gloucestershire–Oxfordshire border. Thomas Henry Ashton became deeply involved in the Heythrop Hunt, serving as its Master—a role that put him in charge of overseeing the hunt and its operations. Remarkably, he held this position for an impressive eighteen years, guiding the hunt through some of its most challenging periods, including the disruptions caused by the Second World War.

During the years of the Second World War hunting, like many other leisure activities, faced considerable difficulties, including restrictions on land use, manpower, and resources. However, Thomas Henry Ashton’s leadership helped the Heythrop Hunt survive these challenges and was able to continue its operations. His dedication to the sport and his ability to maintain its traditions during a tumultuous period earned him a respected place in the hunting community.

Unlike his predecessors, whose legacies were tied to industry, philanthropy, and politics, Thomas Henry Ashton’s legacy was largely shaped by his contributions to the rural lifestyle and hunting culture of the British aristocracy. While the family’s industrial roots remained an important part of their history, the 2nd Baron Ashton of Hyde’s life represented a shift towards more traditional pursuits of the English upper class, embracing the pastoral and sporting aspects of country life in Gloucestershire.

His son, Thomas John Ashton (1926-2008), the 3rd Baron Ashton of Hyde was keen on hunting too, but after doing his national service and going to university, he joined Barclays Bank under a scheme which allowed accelerated promotion to the level of director for young men of appropriate background. According to his obituarist, when he worked in Oxford during the late 1950s, he would go into the office early to dictate letters and then go hunting; returning to the office later in the day to sign his correspondence. When he inherited Broadwell Hill in 1983, however, he put Broadwell Hill on the market, and even though it did not sell, he seems not subsequently to have lived there it was eventually made over to his son, Thomas Henry Ashton (b. 1958), the 4th and present Baron Ashton of Hyde, who had a career in the insurance industry before inheriting the peerage. Although hereditary peers no longer sit in the House of Lords as of right, he was elected in 2011 to fill one of the 90 seats reserved for them, and since 2014 he has been a minister in the coalition and Conservative governments.

Pole Bank Hall, Hyde, Cheshire

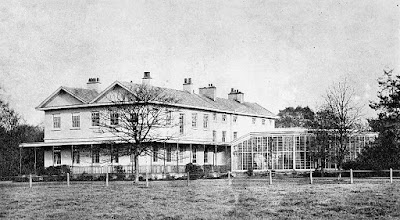

| Fig 4: The image titled “Pole Bank Hall: an early 20th century view of the entrance front from an old postcard” appears in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog, which documents the Ashton family’s legacy in Hyde. Pole Bank Hall was built around 1820 by Samuel Ashton (1773–1849) and later inherited by his son Benjamin Ashton (1813–89). The house was eventually given to the people of Hyde in 1943 and now serves as a care home. You can view the image and explore its historical context on the Landed Families blog. |

This property is dated from the early 19th century. It is a red brick house in Hyde that presents a fascinating blend of classical design and unfortunate later alterations. The house’s entrance front, facing southeast, is a dignified composition of three bays that are framed by brick pilasters, and topped with a striking pedimented Ionic porch made of stone. The porch, adorned with wreaths in the frieze, adds a sense of grandeur to the otherwise simple, brick façade, showcasing the classical influences typical of the Georgian and early Victorian periods. This architectural detail would have likely been a symbol of prestige, signalling the homeowner’s taste and status in society.

On the southwest elevation, the original design included five bays, with the central bay featuring a shallow bow. This curve would have provided a graceful architectural feature, offering enhanced views of the surrounding parkland. However, later modifications have disrupted this elegance as the house has been extended to the north, and a windowless, flat-roofed block has been added to the west. This addition, which is stark in contrast to the original design, has been described as resembling a crematorium, a jarring visual interruption to the otherwise balanced and historically resonant architecture of the main house.

At one time, the southwest side of the house boasted lovely views across a park that was once dotted with greenhouses and enhanced the property’s charm and appeal. These greenhouses would have provided the residents with fresh produce and ornamental plants, which contributed to the self-sufficiency and aesthetic beauty of the estate. Today, the park still features a lake, which remains a scenic aspect of the property. However, the once open and panoramic views have been obscured by trees that have since grown, altering the relationship between the house and its landscape.

In 1943, the house was given to the people of Hyde. It was transitioned from a private residence to a public asset. It now functions as a care home, marking a significant shift in its purpose. The transformation from an elite country house to a facility for public service reflects the changing social and economic landscape of the mid-20th century, as grand estates often found new roles in a society that increasingly prioritised communal welfare over private luxury.

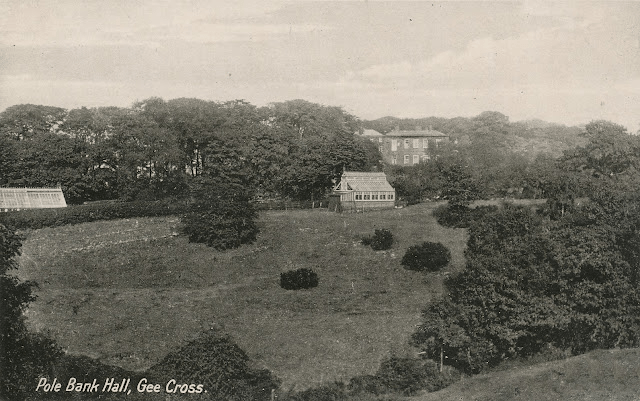

| Fig 5: Pole Bank Hall: an early postcard of the park, showing the side elevation of the house. appears in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog, which documents the Ashton family’s legacy in Hyde. Pole Bank Hall was built around 1820 by Samuel Ashton (1773–1849) and later inherited by his son Benjamin Ashton (1813–89). The house was eventually given to the people of Hyde in 1943 and now serves as a care home. You can view the image and explore its historical context on the Landed Families blog. Descent: Samuel Ashton (1742-1812); to son Benjamin Ashton (1813-89); to nephew, (Arthur) Godfrey Burchardt-Ashton (b. 1854); sold to Thomas Beeley; to son Thomas Carter Beeley (d. 1909); sold c.1910 to George F. Byrom (d. 1942); bequeathed to Hyde Borough Council. |

Newton Lodge, Hyde, Cheshire

The stone villa was built around 1820 and is a quintessential example of early 19th-century architecture, that is characterised by a simple and classical elegance. The house is composed of three bays and stands two storeys tall. It is designed in a plan that is a square which emphasises balance and symmetry, the hallmarks of Georgian architectural principles.

The front entrance features a projecting central section, distinguished by a semi-circular Ionic porch. This porch, with its stately columns and curved design, lends an air of grandeur to the otherwise understated façade. Above the porch, a plat band runs horizontally across the building, extending the line of the porch’s entablature and visually uniting the elements of the structure, creating a cohesive and harmonious look.

In contrast to the ornate detailing of the front entrance, the side elevations of the villa are markedly plain. Their unadorned surfaces contribute to the overall restraint and refinement of the design, which is in keeping with the minimalist aesthetic of the period. This simplicity underscores the villa’s elegant proportions without distracting from the architectural focus of the projecting entrance.

The rear of the villa, a service wing provides a functional space for the household’s day-to-day operations, which allows the main living areas to retain their formal and refined atmosphere. This service wing would have housed the kitchen, storage rooms, and quarters for domestic staff, ensuring that the villa’s primary façade remained uncluttered and reserved for welcoming guests.

The villa’s design, with its classical porch and austere side elevations, reflects the architectural trends of the time, where simplicity and order were highly valued. The building’s understated elegance stands as a testament to the restrained beauty that defined early 19th-century residential architecture.

| Fig 6: The image titled “Newton Lodge, Hyde: entrance front c.1910, from an old postcard” is sourced fromTameside Archives and featured in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog. Newton Lodge was a three-bay, two-storey stone villa built around 1820 by James Ashton (1777–1841). It had a semicircular Ionic porch and a service wing at the rear. The house and grounds were donated to the town of Hyde by Eveline and Amy Ashton, daughters of Charles James Ashton, and opened as a public park in 1904. Sadly, the house was demolished in 1938 and replaced by Bayley Hall. |

Fig 7: Newton Lodge, Hyde, from an old postcard. The house and grounds were given to the town of Hyde by the daughters of C.J. Ashton and opened as a park in 1904, but the borough authorities demolished the house in 1938 and replaced it with Bayley Hall. You can view the image and explore its historical context on the Landed Families blog.

Descent: built for James Ashton (1777-1841); to son, John Ashton (1800-44); to son, Charles James Ashton (1830-91); to widow, Mary Eliza Ashton (1845-93); to daughters, Eveline Mary (1875-1952), later wife of Rev. Arthur Henry Talbot (1855-1927) and Amy Elizabeth (1877-1960), later wife of Lt-Col. Ellis Holland (1854-1920), who gave it to Hyde Borough Council in 1902.

Little Onn Hall, Church Eaton, Staffordshire

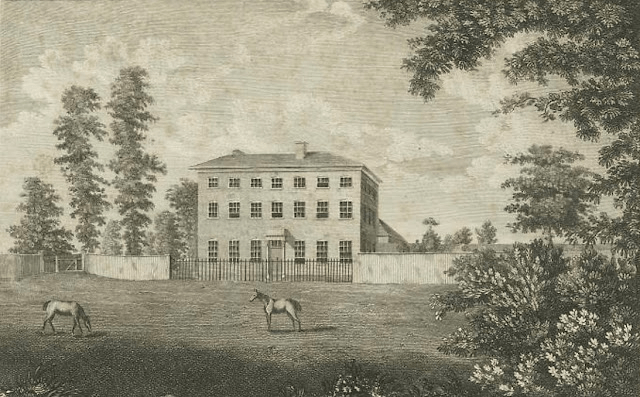

| Fig 8: The image titled “Little Onn Hall: unpublished engraving commissioned by Stebbing Shaw” is sourced from the William Salt Library in Stafford and featured in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog. It depicts the earlier incarnation of Little Onn Hall, a late 18th-century house likely built by Henry Crockett (d. 1796) after the estate was acquired by his father Robert Crockett in the mid-1700s. This version of the house was later replaced in the 1850s by a more elaborate Jacobean-style residence commissioned by Lt-Col. Charles James Ashton, with further additions made by his daughters Eveline and Amy Ashton in the 1890s, including a garden design by T.H. Mawson. You can view the engraving and its historical context on the Landed Families blog. |

The manor of Little Onn was first recorded in 1498, identified as a moated site located to the northeast of the current house. It is believed that this was the location of a moated manor house dating back to the 15th or 16th century. Today, remnants of the original structure can still be seen — notably, some above-ground wall sections at the northwest corner of the island within the moat, which are thought to be the remains of the original manor house.

The estate was purchased by Robert Crockett during the mid-18th century. A seven by three bay, two-and-a-half storey late 18th-century house was built here, and it was probably by his son, Henry Crockett (d. 1796), who inherited the building in 1776. Little is known about this house because it was replaced in the 1850s by Lt-Col. Charles James Ashton by an asymmetrical house, its design was of a loosely Jacobean style with crow-stepped gables and a turret with a very pointy roof.

| Fig 9: Little Onn Hall: entrance front: the house of the 1850s is to the right; the extensions of the 1890s to the left. The image is featured in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog. Landed Families blog. The original source is unknown. |

When Col. Ashton died in 1891 the building was inherited by his widow (d. 1893) and then by his two young daughters, making some rather uninspiring additions to the house. These new additions were in a freer Jacobean style by an unknown architect. These new additions included a new porch and a large, mostly single-storey range to its left that sports a big bay window. They also and more happily commissioned a new garden design from T.H. Mawson, then early in his career was able to rapidly build a reputation as one of the foremost garden designers. The date of these works is not absolutely clear, but even though the sisters were only 18 and 16 in 1893, it would appear that the changes were made sooner rather than later in their ownership.

Mawson’s garden scheme wasn’t fully executed because the sisters spent so much on the additions to the house that they ran out of money, but the main areas of his plan were carried out and remain one of his best-preserved schemes. Mawson created a terrace around the house excavating the land where it did not fall naturally and moved the approach drive from the north to the west side. The formal gardens were created close to the house, where a series of square stone summerhouses which marked the boundary between the gardens and the pasture land beyond, were planted with specimen trees. At the north-east of the house a medieval moat site was incorporated into the garden. The island in the moat was given a rustic summerhouse with tiny Gothic windows, rustic timbering, and a wooden tiled roof, and it was intended to create three bridges across the moat, but it is not clear whether these were ever built.

| Fig 10: Little Onn Hall: garden design by T.H. Mawson, c.1895. The image is featured in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog. Landed Families blog. The original source is unknown. |

Descent: Robert Crockett (d. 1776); to son, Henry Crockett (d. 1796); to son, Henry Crockett (d. 1833), who sold c.1830 to James Ashton (1777-1841); to son, John Ashton (d. 1844); to son, Lt-Col. Charles James Ashton (1830-91), who rebuilt the house; to widow, Eliza Mary Ashton (1845-93); to daughters, Eveline Mary and Amy Elizabeth Ashton, who sold c.1907 to Tyrell William Cavendish (d. 1912 in the Titanic disaster); to widow, Julia Florence Cavendish (d. 1963) who sold to William Dickens Hayward (d. by 1939); to widow….sold 1971 to Ian Kidson (d. 1998); to widow (d. 2004); sold 2005 to David George Bradshaw (b. 1968).

Broadwell Hill, Gloucestershire

| Fig 11: Broadwell Hill: the garden front. The image is featured in the Landed Families of Britain and Ireland blog. Landed Families blog. The original source is unknown. |

Broadwell Hill, a small freehold estate changed hands several times during the 19th century. It was purchased c.1876 by Capt. Piers Thursby. Unfortunately, nothing is known about the house which accompanied the property during this period, but it was probably no more than a comfortable gentleman farmer’s house. In 1879, Thursby employed Ewan Christian to replace the building with a large, loosely Jacobean, gabled house that had tall chimneys and bay windows facing the garden which bears a considerable similarity to his earlier Abbotswood.

When Thursby’s widow died in 1912 the house was sold and then changed hands several times before being purchased by Thomas Ashton (later 2nd Baron Ashton of Hyde) in 1929. Eric Cole of Cirencester extended the original house in 1938. The new wing was built at an angle to the southwest and gave the house a rather unusual plan. The principal objective of this extension was presumably to provide some reception rooms and bedrooms with a better aspect, since the main rooms of the original house faced east. The new wing was lower than the main block and masses with it fairly successfully but is executed in the rather mechanical Cotswold Tudor style associated with Cole. Lord Ashton of Hyde died in 1983 and the house was offered for sale shortly afterwards, but it remains in the family.

Descent: Barker family; sold 1802 to Lee Compere; sold 1824 to Robert Beman; sold 1874 to Albert Clifford sold c.1876 to Capt. Piers Thursby (1834-1904), who rebuilt the house; to widow, Mary Thursby (nee Godman) (1839-1912); sold to Charles Slingsby Peirse-Duncombe (1870-1925); sold to Rev. Cecil Graham Moon (1867-1948); sold 1929 to Thomas Ashton (1901-83), 2nd Baron Ashton of Hyde, who extended the house; to son, Thomas John Ashton (1926-2008), 3rd Baron Ashton of Hyde, who transferred it to his son, (Thomas) Henry Ashton (b. 1958), 4th Baron Ashton of Hyde

References:

Burke’s Landed Gentry, 1898, vol. 1, pp. 34-35; Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage, 2003, pp. 159-60; T. Middleton, Annals of Hyde and district, 1899, pp. 146-54; VCH Glos, vi, p. 53; Sir N. Pevsner, The buildings of England: Staffordshire, 1974, p.104; D. Verey and A. Brooks, The buildings of England: Gloucestershire – The Cotswolds, 1999, i, p. 202; C. Hartwell, M. Hyde, E. Hubbard and Sir N. Pevsner, The buildings of England: Cheshire, 2011, pp. 409-14.

Location of Archives

Ashton family, Barons Ashton of Hyde: family papers, chiefly of Thomas Ashton (1818-98) [Manchester Archives and Local Studies, M107]; Sussex estate deeds and papers, 16th-19th cents [East Sussex Record Office, SAS-AN]

Websites & Images:

Fig 1: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 2: Manchester Library

Fig 3: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 4: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 5: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 6: Tameside Archives

Fig 7: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 8: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 9: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 10: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.

Fig 11: Landed Families of Britain and Ireland Blog.