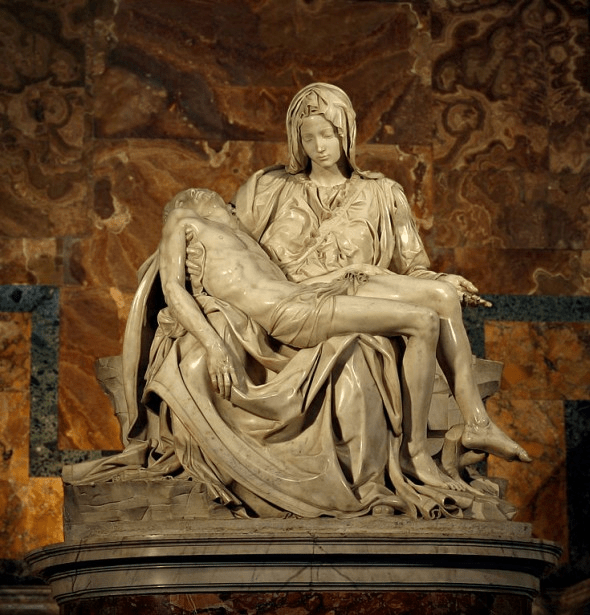

Michelangelo, Pieta, c. 1498-1500, marble

The Pietà is one of the most poignant and enduring subjects in Christian art. Depicting the Virgin Mary holding the lifeless body of Jesus after the Crucifixion, this image has moved generations of artists to capture its sorrow and grace.

More than a religious icon, the Pietà speaks to universal themes of loss, love, tenderness, and sacrifice. In this article, we’ll explore what makes the Pietà so powerful, highlight famous interpretations, and share resources for further discovery.

What Is a Pietà?

The word Pietà comes from the Italian for “pity” or “compassion.” Unlike a Lamentation scene—which often includes multiple figures—the Pietà depicts only Mary and Jesus.

This pared-back composition heightens the intimacy of their bond: a mother’s grief and a saviour’s sacrifice, rendered in quiet, contemplative stillness

Famous Examples of the Pietà in Art

Michelangelo’s Pietà (1498–1499)

Located in St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

Michelangelo’s marble Pietà is perhaps the most celebrated. Created when he was just in his early twenties, the sculpture is renowned for its exquisite detail: the serene face of Mary, the delicately carved folds of her robes, and the youthful, graceful body of Christ.

It’s the only sculpture Michelangelo ever signed — a mark of pride etched across Mary’s sash. The composition’s pyramidal structure and idealised beauty reflect both classical influence and spiritual reverence, making it a cornerstone of High Renaissance sculpture.

Reference:

Vatican Museums – Michelangelo’s Pietà

Rogier van der Weyden, Lamentation (Pietà) (c. 1460)

Museo del prado collection

Van der Weyden’s painted interpretation of the Pietà replaces marble with brushstroke’s yet loses none of the emotional force. Unlike the serene restraint of sculpted versions, Mary’s visible anguish anchors the composition in a raw, human dimension. The tender arrangement of figures — their gestures, facial expressions, and closeness — draws the viewer into a moment of shared sorrow, rendering grief not just sacred, but profoundly real.

Reference:

El Greco, Pietà (1571–1576)

Philadelphia Museum of Art

El Greco’s Pietà stands out for its vivid palette and dynamic composition. Unlike Michelangelo’s serene and sculptural version, El Greco’s painted scene pulses with emotional turbulence. The Virgin Mary’s grief is accentuated by swirling forms and elongated figures, hallmarks of the Mannerist style. Dramatic light and stormy skies deepen the sense of spiritual unrest, transforming the Pietà from quiet mourning into a visual lament — urgent, expressive, and transcendent.

Reference:

El Greco’s Pietà (c. 1571–1576)

Painted shortly after El Greco’s arrival in Rome, this small tempera-on-panel work channels the emotional gravity of the Pietà through the lens of Mannerism. The composition, triangular and tightly arranged, draws clear influence from Michelangelo’s sculptural version, yet El Greco’s expressive brushwork and vivid palette make it uniquely his own. Elongated figures, dramatic contrasts, and a stormy backdrop heighten the sense of spiritual unrest, transforming the traditional scene of mourning into a dynamic meditation on grief and transcendence.

El Greco’s Pietà (c. 1571–1576) while listed in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is not currently on public view. As with many historic works, its display is subject to rotation, conservation, or loan. Though unseen by most visitors, its vivid emotional resonance continues to speak through reproductions and scholarly reflections — a quiet reminder of how grief and devotion transcend visibility.

Annibale Carracci, Pietà (1600–1602)

Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

Carracci’s interpretation features dramatic lighting and a deeply sorrowful Mary, reflecting the Baroque focus on intense emotion. Drawing inspiration from Michelangelo’s sculptural Pietà, Carracci adds angels and earthy textures to heighten the intimacy and pathos of the scene.

Reference:

Though not currently listed in the museum’s online catalogue, Carracci’s Pietà remains part of the Farnese Collection at the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples. Like many historic works, its visibility may vary due to conservation or curatorial rotation.

Why Artists Return to the Pietà

Throughout art history, the Pietà has remained a compelling subject because it combines:

- Human emotion: A universal theme of a parent mourning a child.

- Spiritual devotion: An image of redemptive sacrifice central to Christian belief.

- Artistic challenge: The opportunity to convey compassion, anatomy, and drapery in a single, powerful composition.

Each version offers a unique interpretation, shaped by its time, culture, and medium.

Further Reading & References

If you’d like to explore more:

- Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion

- James Hall, Michelangelo and the Reinvention of the Human Body

- Richard Viladesau, The Pathos of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts

Have you seen a Pietà that moved you? Feel free to share your thoughts or favourite examples in the comments. Art has a unique way of helping us explore both sorrow and hope.

All references are used respectfully for educational storytelling. See About Me for full source credits.

Subscribe for fresh posts on art, poetry, and thoughtful storytelling — delivered with care.

References:

Image:

Websites: