This post is inspired by the research and reflections of Denise Jones, as featured in “A Suffragette Detective Story” on Selvedge Magazine’s website. Her work continues to illuminate the legacy of textile protest with clarity and compassion.

A Mended Resistance

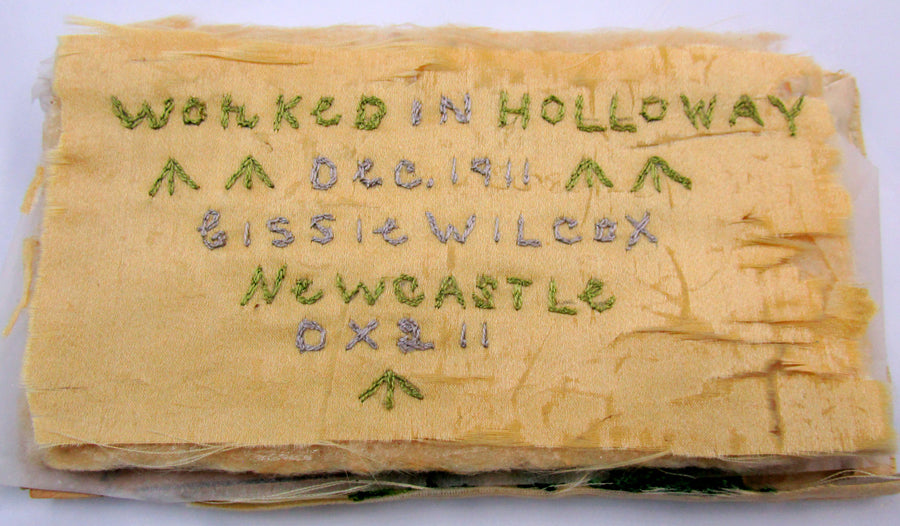

Fig 1: Cissie Wilcox, an embroidered panel (December, 1911). All images © Museum of London. Available via the Museum of London’s online collection and featured in Denise Jones’s article “A Suffragette Detective Story” on Selvedge Magazine’s website.

This embroidered panel by Cissie Wilcox, was created in December 1911 whilst imprisoned in Holloway Gaol. A poignant example of suffragette resistance through textiles. It features purple and green silk embroidery, including her prison wing and cell number (DX2.11), and symbols like the prisoner’s arrows—marking her protest against the treatment of women during the suffrage movement.

This piece is part of the Museum of London’s collection, and its story is beautifully explored in a guest article by Denise Jones on the Selvedge Magazine website. The article delves into the emotional and political significance of Cissie Wilcox’s work, the materials she used, and the context of her imprisonment following the window-smashing campaign of 1911.

What and Where was Holloway Gaol?

Holloway Gaol, later known as HM Prison Holloway, was a historic women’s prison in North London that played a central role in the suffragette movement. After becoming a female-only institution in 1903, it housed many notable activists, including Emmeline Pankhurst and Constance Lytton. Suffragettes imprisoned there created embroidered protest pieces that survive as powerful symbols of resistance,

You can explore this story in Denise Jones’s article for Selvedge Magazine, and through the Museum of London’s collection, which preserves Cissie Wilcox’s panel and its quiet defiance through stitch.

Within the Museum of London’s Suffragette Fellowship Collection lies extraordinary embroidered relics from Holloway Prison—handkerchiefs and textile fragments bearing delicate stitches and bold histories. Crafted in early-1912, these pieces are threaded with the names of imprisoned suffragettes and worked in the movement’s signature colours: purple, white, and green.

Fig 2: Cissie Wilcox, an embroidered handkerchief (January, 1912). Worked in Holloway Prison and gifted to fellow suffragette Janie Terrero, this piece features the names of fifteen women imprisoned for window-smashing protests. Embroidered in purple and green silk—colours of the WSPU—it stands as a quiet act of resistance and solidarity. All images © Museum of London. As featured in Denise Jones’s article “A Suffragette Detective Story” on Selvedge Magazine’s website.

These embroideries were stitched during associated labour—prison sewing sessions where suffragettes either knitted or sewed authorised items. It’s believed the thread and fabric were covertly smuggled in, turning these objects into discreet statements of solidarity.

Fig 3: Cissie Wilcox, package fragments (December, 1911). Photograph: Denise Jones. This embroidered silk fragment—once part of a concealed package—was worked in Holloway Prison and may have been used to smuggle a letter or personal item. The backing fabric was cut away in haste, revealing cardboard from a Bloomsbury fruit box and a hand-embroidered rose, possibly repurposed from a bell pull. A quiet act of defiance stitched into concealment. As featured in Denise Jones’s article “A Suffragette Detective Story” on Selvedge Magazine’s website.

This image (shown above) immediately caught my eye—a truly stunning example of visual storytelling. Its composition, light, and detail draw you in at first glance, offering not just beauty but a sense of atmosphere and emotion. It’s one of those rare images that lingers in your mind long after you’ve looked away.

Stories in Stitch & Fabric

One striking example is a handkerchief (shown above fig 2) embroidered by Cissie Wilcox, listing fellow prisoners and dates of their sentences. These names recall personal sacrifices—many women endured hunger strikes and force-feeding while incarcerated.

The handkerchief offers its first clues through the stitched prison sentences and dates in three of its corners, with a dedication to a Mrs Terrero. It was a gift from the women whom Cissie names in the lower half of the cloth. After searching through Votes for Women and local newspaper archives, Denise Jones (the author of the article in Selvedge Magazine) discovered that Cissie had indeed been arrested and imprisoned on the very dates she embroidered—confirming her involvement as a militant member of the Newcastle branch of the WSPU. This is echoed in the inscription in the fourth corner: the WSPU motto “Deeds not Words” alongside the word “Newcastle,” stitched onto a small fabric fragment.

Fig 4: Janie Terrero (c. 1912). © Museum of London. A portrait of the militant suffragette wearing her Hunger Strike Medal and Holloway brooch, captured during the height of her activism. Terrero was imprisoned in Holloway in 1912 for window-smashing protests and endured force-feeding during hunger strikes. Her resilience and quiet courage are echoed in the embroidered works she created and received. As featured in Denise Jones’s article “A Suffragette Detective Story” on Selvedge Magazine’s website.

Fig 5: Janie Terrero, embroidered panel (1912). © Museum of London. Worked in Holloway Prison to commemorate twenty women—including Terrero herself—who endured force-feeding during the April 1912 hunger strike. The panel, stitched in suffragette colours of purple and green, stands as a testament to solidarity and protest through craft. As featured in Denise Jones’s article “A Suffragette Detective Story” on Selvedge Magazine’s website.

Denise Jones describes how she feels holding these embroideries it “sends a tingle through my nervous system. Unlike the digital archive I can sense the physicality of the materials, their dirtiness, the scale of them and also get under the skin of the maker. I can begin to understand how she thought and how she fiddled with the cloth and thread, what decisions she made. I can look at the back of the work and understand her hand. I am touching, looking and thinking about them and about her.”

Political Threads

These embroideries go beyond personal artistry—they are political documents. Using suffragette colours and signatures, they affirm shared identity and resistance within prison walls. More than decoration, they served as gifts, memorials, and markers of mutual recognition among women demanding change.

Step into the Collection

The Museum of London houses the Suffragette Fellowship Collection, which comprising textiles, banners, photographs, pamphlets, and personal papers from the early 20th‑century campaign. It provides rich context for understanding the lived realities of those who fought for the vote.

Visiting the museum offers a rare chance to connect with these intimate artefacts. In an age where we often view suffrage through marches and speeches, these humble cloths provide a quieter, tactile form of protest—where embroidery became resistance.

Why it matters:

These suffragette embroideries preserve stories that might otherwise fade—hand‑stitched memories of courage, solidarity, & creativity in the face of repression. They reveal how needlework served as a subtle form of protest, preserving identity and forging connections where voices were silenced.

Disclaimer: I have made every effort to reference and credit the original article and sources used in this post. If any citations are incomplete or if you are the author of any of the material referenced and would like it amended or removed, please feel free to get in touch.

Stay Connected – Subscribe Now!

If you’ve enjoyed reading this post and want to stay updated with more content like this, consider subscribing! You’ll receive notifications about new articles, behind-the-scenes insights, and special updates straight to your inbox. It’s a great way to stay connected and support this project. Just hit the subscribe button – I’d love to have you along.

References:

Images:

Fig 1: Selvedge Magazine

Fig 2: Selvedge Magazine

Fig 3: Selvedge Magazine

Fig 4: Selvedge Magazine

Fig 5: Selvedge Magazine

Websites: