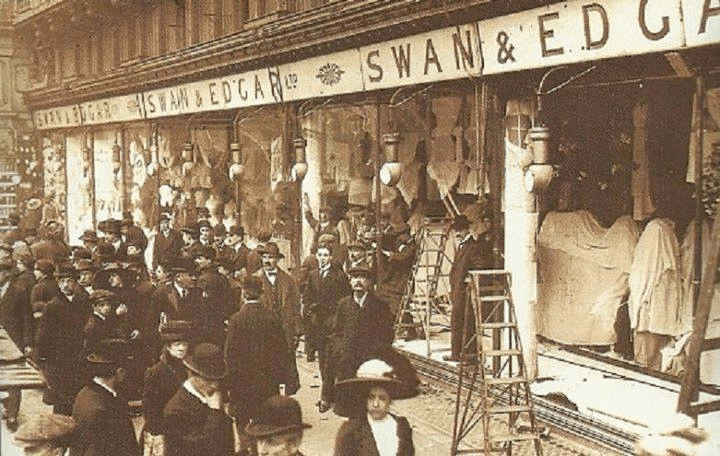

This image was found on the Past Tense blog’s “suffragettes” page, The original image source is unknown. It offers a rich archive of posts exploring radical moments in women’s suffrage history — especially the militant actions of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU).

Notable Entry: “Today in London Smashing History, 1912

- This post recounts the window-smashing campaign of March 1912, quoting The New York Times:

“Never since plate glass was invented has there been such a smashing and shattering of it…” - It describes how suffragettes targeted West End shopfronts, including Swan & Edgar, in a coordinated act of civil disobedience.

- The post includes a striking image of broken windows and links to other related entries on suffragette tactics.

Other Entries:

- Stories of Muriel Matters flying a suffragette airship over London in 1909.

- Accounts of Sylvia Pankhurst’s arrest during the 1914 International Women’s Day march.

- Reflections on Jessie Craigen, a working-class suffragist and public speaker.

It’s a treasure trove of lesser-known stories and vivid retellings.

On 1 March 1912, the streets of London rang with the sound of breaking glass—not from mindless destruction, but from a bold and calculated act of political protest. The suffragette window-smashing campaign, orchestrated by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), was one of the most dramatic strategies used in the long battle for women’s suffrage. For many of the women involved, it was a way to shatter not just shopfronts, but the silence and inaction that had for too long met their demands for political equality.

This radical shift in tactics came after years of frustration. Peaceful protests, petitions, and demonstrations had failed to move the government. Despite women’s growing roles in education, public service, and the workforce, they remained voiceless at the ballot box. The suffragettes responded with a new strategy: if their voices continued to be ignored, then the property the government so dearly valued would become the target.

On that March day, over 150 women participated in a carefully coordinated attack. Armed not with weapons of war, but with hammers, stones, and hatchets concealed in handbags and coat sleeves, they struck at the heart of London’s commercial and political districts. Department stores like Selfridges and Fortnum & Mason, as well as government offices including the Home Office, saw their windows smashed in unison.

This was not random vandalism—it was protest with purpose. As one suffragette famously declared: “I am a lawbreaker because I want to be a lawmaker.”

Arrests came swiftly. Many women were imprisoned, and several began hunger strikes while incarcerated—leading to further suffering through force-feeding. But the message was unmistakable: if glass was the barrier between women and political power, they would break it.

More than 270 properties were damaged during the campaign, and over 120 women were arrested—including Charlotte Blacklock, who was later subjected to force-feeding after going on hunger strike in prison. This wave of militant action was carefully planned to overwhelm the prison system and compel the government to confront the suffragettes’ demands.

The campaign stirred controversy. Even within the suffrage movement, opinions were divided. Some feared the militant approach would alienate public support. Others believed it was a necessary escalation in a fight that had already stretched for decades with little progress.

Today, the smashed windows of 1912 live on as a powerful symbol. They represent the fragility of the systems that excluded women, and the courage of those who dared to disrupt them. The suffragettes didn’t just break glass—they broke silence, broke barriers, and changed history.

Further Reading:

- The Bow Street Police Museum’s “Shattering Suffrage” article offers a vivid account of the 1912 window-smashing campaign led by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Here are some key highlights from the piece:

Scale and Symbolism of the Campaign

- Over 150 suffragettes took part in coordinated attacks across London’s West End, targeting sites like the Savoy Hotel, Hotel Cecil, and the Aerated Bread Company.

- The campaign was designed to disrupt societal norms and draw attention to the urgency of women’s suffrage.

- Lillian Ball famously engraved her toffee hammer with the phrase: “Better Broken Windows than Broken Promises.”

Police Response and Legal Consequences

- Despite prior warnings, police were overwhelmed. 126 women were arrested, and 76 received sentences of hard labour.

- Suffragette Kitty Marion was sent to Winson Green Prison due to overcrowding at Holloway and went on hunger strike.

- Bow Street Court played a central role in processing arrests, with suffragettes like Victoria Lidiard recounting their experiences there.

Prison as Protest Space

- Holloway Prison became a site of resistance, where women embroidered banners and handkerchiefs with the names of hunger strikers.

- These artifacts, now held by institutions like the Museum of London, reflect the suffragettes’ resilience and solidarity.

The article also supports a walking tour called Reform, Rebel, RIOT! that explores civil disobedience in Covent Garden — including the suffragettes’ legacy.

2. The Historical Writers’ Association page for Secret Missions of the Suffragettes – Glass Breakers & Safe Houses by Jennifer Godfrey offers a compelling overview of the 1912 protest and its covert underpinnings.

Key highlights from the book description

- Over two nights in March 1912, more than 250 women were arrested for smashing windows of shops and offices across London.

- Participants ranged from Ethel Violet Baldock, a 19-year-old maid, to Mrs Hilda Eliza Brackenbury, a 79-year-old safe house owner.

- The protest was orchestrated by Emmeline Pankhurst in response to the government’s refusal to include women in the reform bill.

Behind-the-Scenes Activism

- The book explores suffragette safe houses, rest homes, and daring escapes from police surveillance.

- It delves into their use of disguises, codes, aliases, and even self-defence training.

- These tactics reveal a network of friendships and collaborations that shaped the suffrage movement’s resilience and ingenuity.

It’s a rich resource for understanding how glass-breaking wasn’t just a public spectacle — it was part of a deeply strategic and emotionally charged campaign.

References:

Websites:

Bow Street Museum if Crime & Justice

Historical Writers’ Association