Land, labour, fields, paths, and memory

Before the mills, chapels, and terraces transformed the landscape, Gee Cross and Werneth Low belonged to a much older pattern of land organisation: the manorial system. For centuries, this framework shaped how people lived, worked, and interacted with the land. Its traces remain visible today in field boundaries, footpaths, and place-names.

This post gathers the key elements in one place — the historical background, the local evidence, and the maps and field names that help us read the earlier landscape.

The Manorial System: a local structure

In medieval England, land was arranged into manors. A manor was not simply the property of a lord; it was a functioning economic unit made up of:

- Strips of arable land

- Meadows and pastures

- Upland grazing and common land

- A small community of tenants

Gee Cross and the slopes of Werneth Low sat within the manorial territories of Hyde and Mottram, themselves part of the wider Longdendale landscape. Few people owned land outright. Instead, they held customary rights — to cultivate certain strips, graze animals, gather fuel, or use shared land according to long‑established local practice.

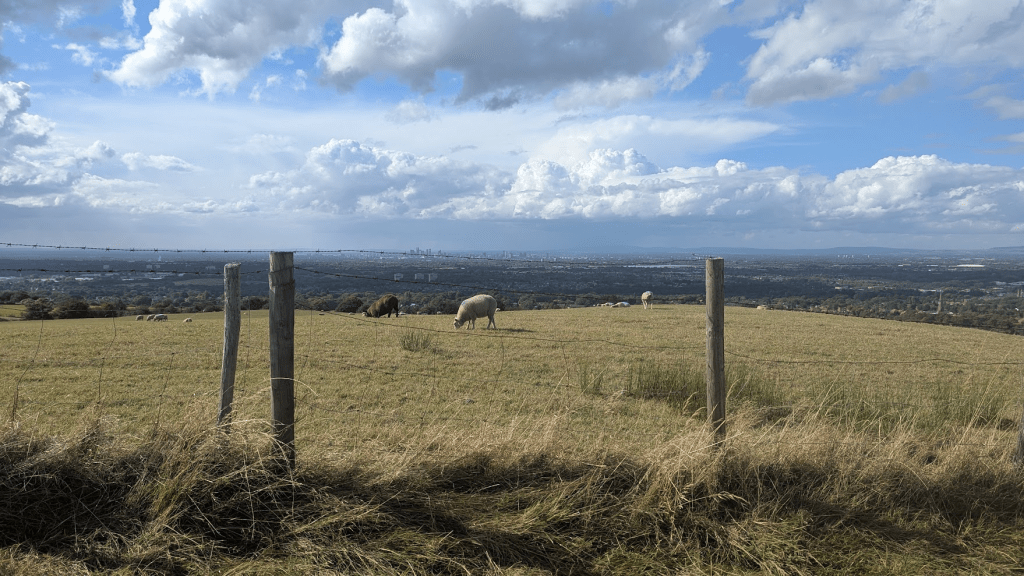

Werneth Low as working land

Werneth Low was never an empty or unused hill. Its height, exposure, and rougher ground made it ideal for upland pasture. Such land was rarely enclosed early and was typically used for:

- Grazing cattle and sheep

- Seasonal rather than permanent farming

- Providing poorer households with access to grass and fuel

This pattern aligns closely with what landscape historians describe as common or semi‑common land, often preserved longest on higher ground. The continued openness of Werneth Low well into later centuries strongly suggests it functioned as shared grazing land under the manorial system.

Gee Cross: a small agricultural hamlet

Gee Cross likely began as a scattered hamlet, its name hinting at a crossing point — perhaps where routes met or boundaries converged. Within the manorial structure, such settlements were not independent villages but working communities tied to the surrounding fields and commons.

Daily life would have revolved around:

- Smallholdings linked to strips of land

- Mixed farming and domestic production

- Seasonal agricultural rhythms

- Duties owed to the manor

Homes were places of work as much as shelter. Spinning, mending, food preparation, and craft activity took place alongside farming — an important backdrop for understanding later cottage industries and the area’s textile traditions.

Field names: clues preserved in maps

Nineteenth‑century tithe maps are invaluable for understanding earlier land use, often preserving field names that reflect much older practices.

Around Gee Cross and Werneth Low, the Hyde tithe maps (c.1838–1842) record names such as:

- Low Field / Lowe Field

- Bent Field (bent grass = upland grazing)

- Rough Field / Rough Pasture

- Hurst / Hursts (from Old English hyrst, meaning wooded hill)

- Over Field / Nether Field (upper and lower divisions)

- Great Meadow / Little Meadow

These names are functional, not decorative. They point to:

- Strip farming (Over/Nether)

- Seasonal grazing (Bent, Rough)

- Wood‑pasture and marginal land (Hurst)

Historians routinely use such names as evidence of continuity from medieval land use into later centuries.

Paths and routes still underfoot

Many footpaths around Gee Cross and Werneth Low follow routes that pre‑date modern roads. They offer some of the clearest clues to the earlier manorial landscape.

Key features include:

- Ridge‑aligned paths typical of livestock movement

- Sunken lanes worn down by centuries of use

- Irregular, boundary‑following routes unlike later straight enclosure roads

When compared with the Ordnance Survey First Edition maps (1840s–50s), many of these paths show striking continuity. They often align with:

- Parish boundaries

- Old field edges

- Watershed lines

All are recognised indicators of medieval land organisation.

Mapping the landscape

Several historic maps help reveal these patterns:

I’ve written a separate post about what tithe maps are — read it here.

- Hyde Tithe Map (c.1838–1842)

Shows named fields, land use, and ownership. Held by Cheshire Archives. - Ordnance Survey First Edition Maps (1848–1851) Ordnance Survey

Capture pre‑industrial field patterns and early paths before later development. - Greenwood’s Map of Cheshire (1819) National Library of Scotland

Provides a wider view of the landscape before enclosure was fully completed.

Together, these maps show a landscape shaped long before industrialisation — one organised around shared use, custom, and cooperation.

From manor to modern landscape

By the time mills and terraces appeared, the land around Gee Cross and Werneth Low had already been moulded by centuries of manorial practice. Enclosure, new roads, and industrial development did not create the landscape from scratch; they overlaid and reworked an older system.

Uneven field boundaries, surviving footpaths, and persistent place‑names remain quiet survivals of that earlier world.

Why this still matters

Understanding the manorial system reminds us that land here was once:

- Lived with rather than owned outright

- Shared through custom and mutual responsibility

- Understood through daily, embodied knowledge

In a landscape now shaped by housing pressure and shifting land use, these older patterns invite reflection on belonging, stewardship, and continuity. The past is not distant — it is written into the ground beneath our feet.