This essay forms part of a second phase of landscape writing that widens its focus beyond Werneth Low itself, tracing how early footpaths and desire lines once connected the neighbouring settlements of Gee Cross, Godley, and Mottram in Longdendale. It sits alongside — but separate from — Paths, Footfall, and Erosion, shifting attention from land under pressure to land as collective memory.

Before paths were formalised, they emerged quietly. They were not engineered or imposed; they were discovered through use. Feet, hooves, weather, and repetition shaped the earliest routes across this landscape. Each step tested the ground, and each return confirmed it. Over time, these movements formed a network of lived connection — not lines on a map, but habits written into the land.

How Paths Begin

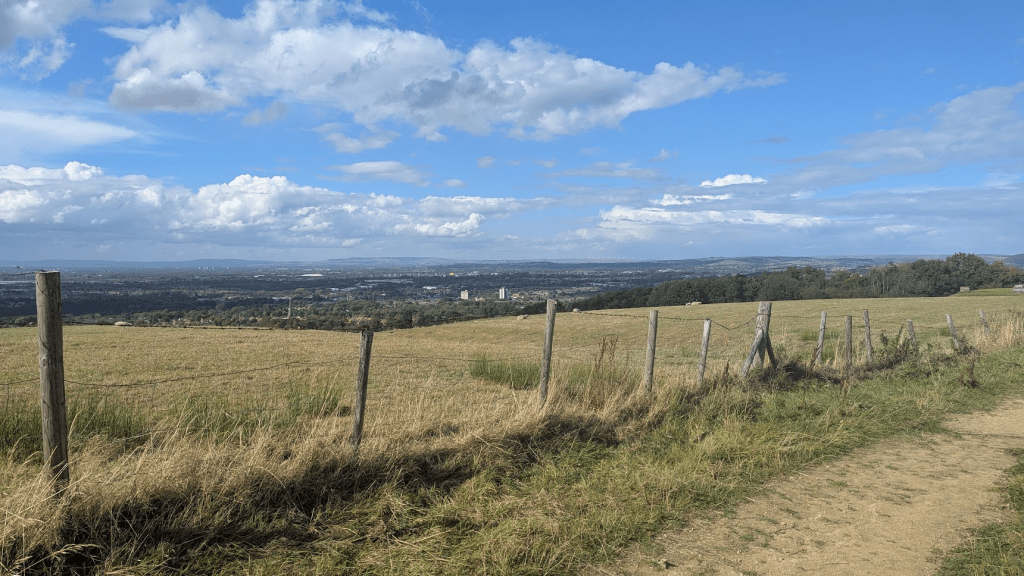

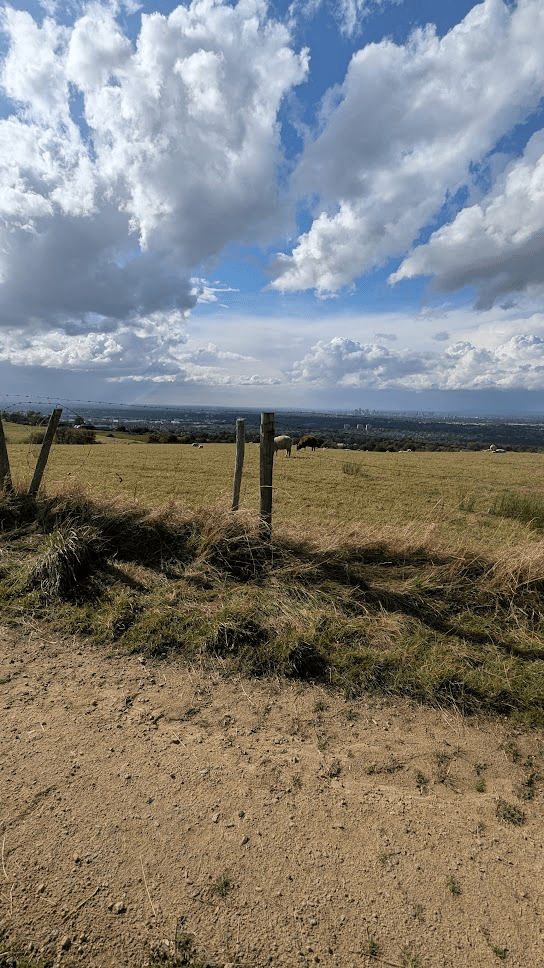

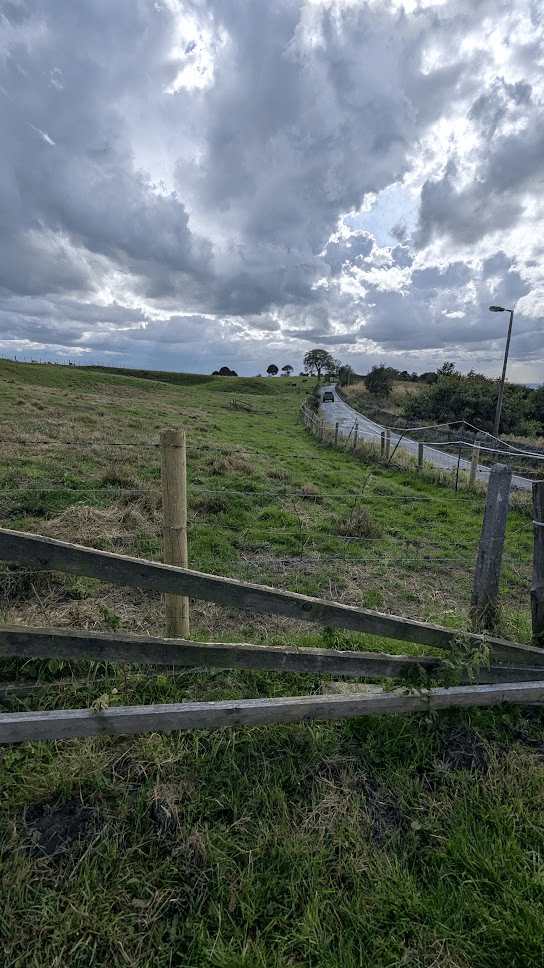

A path begins where resistance is lowest. Where the ground drains well. Where a slope softens. Where shelter is offered, or visibility improves. These small, practical decisions accumulate.

One person walks a route. Then another. Grass thins. Soil compacts. Stones rise to the surface. The land records preference.

This is how desire lines are born — not from authority, but from collective agreement. They are the physical expression of human behaviour repeated until it becomes legible.

What Early Footpaths Reveal About Community Life

The earliest routes between Gee Cross, Godley, Mottram, and the uplands of Werneth Low were shaped by necessity and relationship. People walked to market, to worship, to water sources, to grazing land, or simply to one another. These paths reveal a pattern of interdependence: no settlement existed in isolation.

Historic maps — such as the 1848–1880 Ordnance Survey sheets for Cheshire and Derbyshire — show fragments of these routes still present long after their original purpose faded. Some appear as faint dotted lines across fields; others survive as holloways or narrow lanes bordered by old hedgerows. Their persistence suggests that movement across this landscape was not random but deeply patterned.

What remains today, even in traces, is evidence of cooperation embedded in the ground.

Memory Written Into the Land

Paths are a form of memory. Unlike buildings, they do not insist on permanence. They survive only while they are remembered — walked, chosen, and followed.

Some early routes have vanished entirely, reclaimed by grass or absorbed into farmland. Others linger as subtle signs: a dip in a meadow, a line of compacted earth through woodland, an oddly placed gate that once aligned with a now‑lost track.

These remnants remind us that memory does not always announce itself. Sometimes it waits to be noticed.

Connecting the Low to the Valleys

Werneth Low sits at the centre of this network — not only as a destination, but as a reference point. Paths radiated toward it and away from it, linking upland and valley, exposure and shelter. Movement across the Low required effort and awareness: knowledge of weather, ground conditions, and the safest lines of travel.

The routes that endured were the ones that worked — physically, socially, and seasonally. They represent trust built over generations.

Why Desire Lines Still Matter

Today, desire lines often appear as unofficial shortcuts across parks or verges — signs of impatience or convenience. Historically, they were acts of knowledge. They showed how people actually used land, rather than how they were instructed to use it.

To pay attention to early footpaths is to acknowledge that geography is lived, not imposed. Landscapes are shaped by care, need, and repetition. The land remembers who passed through it, even when we no longer know their names.

Notes on Sources

Here are the direct links you can use for your Notes on Sources section. Each link corresponds to the sources we referenced earlier, and all are safe, public, and accessible.

Ordnance Survey Historical Maps

National Library of Scotland – OS Maps (England & Wales, including 19th‑century editions)

https://maps.nls.uk/

Charles Close Society – Old Series Maps Online

https://charlesclosesociety.org/oldseries

Local Historical Resources

Tameside Local Studies & Archives Centre

https://www.tameside.gov.uk/archives