The Industrial Revolution transformed more than just factories, cities, and everyday life — it also had a profound impact on the world of art. Prior to industrialisation, art largely focused on themes of nature, religion, and classical beauty. However, with the rise of machines, expanding urban environments, and mass production, artists began to respond in powerful and varied ways. Some embraced the spirit of progress and technological change, while others reflected on the loss of rural traditions and exposed the harsh realities of industrial life. This post looks at how the Industrial Revolution gave rise to new artistic movements, altered creative techniques, and reshaped the way people viewed their rapidly changing world.

Fig 1: The Reapers by George Stubbs, image © National Trust Images. Sourced via Art UK.

George Stubbs’ painting, The Reapers (1783), presents an idealised view of the 18th-century British countryside during a period of major agricultural change. Set at harvest time, the scene depicts a group of well-dressed labourers working diligently under the watchful eye of a farmer on horseback. The calm, orderly composition conveys a romanticised vision of rural life, suggesting a harmonious bond between the land and its workers. Yet beneath this tranquil image lies a more complex reality, as the countryside was being transformed by shifting social and economic forces during this era.

An Idealised Rural Scene

At first glance, The Reapers radiates a sense of calm and order. The figures appear industrious but show no signs of fatigue or hardship. The workers are dressed in neat, clean clothing, seemingly unaffected by the physical demands of the harvest. Overseeing the scene, a farmer sits upright on horseback, calmly supervising the reaping. This composition suggests a structured, harmonious rural life, where everyone understands their role in maintaining a natural, orderly system.

In the background, a line of distant elm trees reinforces this sense of balance and control. The trees mark the boundary of the field, subtly indicating that this is a cultivated and carefully managed landscape rather than untamed wilderness. The land itself is divided into tidy, rectangular plots, highlighting human influence in shaping it for agricultural productivity. The straight lines and geometric precision of the fields convey an impression of stability and continuity, as if this ordered way of life has existed for generations and will endure unchanged.

A Vision of Harmony Between Nature and Labour

Stubbs portrayal of the harvest conveys a strong sense of harmony between rural labourers and the natural world around them. Reaping—an age-old symbol of the seasonal cycle and nature’s abundance—is depicted as a timeless, almost ceremonial act. The labourers seem seamlessly connected to the landscape, appearing more like an extension of nature than simply workers performing a job.

Soft, golden light washes over the scene, enhancing its tranquillity. The warm tones of the wheat fields, the gentle contours of the land, and the calm sky create an inviting, peaceful atmosphere. Absent are any signs of the hardships typically associated with farm labour—no gruelling hours, no harsh conditions, no fears over failed crops. Instead, the painting offers an idealised vision where nature is generous, rewarding honest work with stability and comfort. The result is a nostalgic image of rural life: simple, orderly, and perfectly in tune with the rhythms of the natural world.

Social Context: The Changing British Countryside

While Stubbs portrays an idealised vision of rural life, it’s important to view the painting within the wider context of 18th-century Britain. This era was defined by the Agricultural Revolution, a period of dramatic shifts in farming methods, land ownership, and rural labour. The enclosure movement—where common land was consolidated into private ownership—was transforming the countryside. Though it increased farming efficiency, it also displaced many rural workers and contributed to the growth of the urban working class.

In The Reapers, these social and economic tensions are absent. The labourers appear content and industrious, with no sign of the upheaval affecting rural communities at the time. Stubbs depicts the countryside as stable and harmonious, where nature and human labour coexist effortlessly. In this way, the painting presents an idealised and nostalgic image of rural life, one that masks the underlying hardships and profound changes experienced by the agricultural population during the 18th century.

The Influence of Classical Ideals

Stubbs was renowned for his keen interest in anatomy and his precise, detailed depictions of animals, particularly horses. However, in The Reapers, his style leans more towards classical ideals of beauty and harmony. The painting’s composition is carefully balanced and symmetrical, echoing the principles of classical art, where proportion and order are central. The labourers are portrayed in an idealised manner, with graceful, almost heroic postures that elevate their connection to the land.

This classical influence lends the scene a sense of timelessness. The countryside is depicted not merely as a place of labour but as a setting where people attain dignity and purpose through their work with nature. The farmer on horseback embodies more than just supervision—he represents authority and wisdom, guiding the workers in their efforts. This imagery suggests a continuous, harmonious relationship between landowner and labourer, reinforcing the notion that such social structures are natural, enduring, and beneficial for all involved.

The Appeal of the Rural Ideal

The idealised portrayal of rural life in The Reapers held strong appeal for Stubbs’ contemporaries, especially the wealthy landowners who often commissioned such artworks. For these patrons, the painting affirmed their perception of the countryside as a place of stability and prosperity, presenting a romanticised vision that overlooked the social inequalities and hardships faced by the labourers who worked the land.

At a time when industrialisation was beginning to reshape Britain, images like The Reapers offered a reassuring sense of continuity and tradition. Rather than depicting the countryside as a site of upheaval or social tension, Stubbs portrayed it as a timeless landscape where nature and human endeavour coexisted in peaceful, enduring harmony.

A Pastoral Vision

George Stubbs’ The Reapers (1783) presents a highly idealised and harmonious portrayal of 18th-century rural Britain. With its neat, cultivated fields and depictions of diligent, seemingly content labourers, the painting conveys a timeless connection between people and the land. Yet beneath this serene image lies a more complex reality. During Stubbs’ lifetime, the countryside was undergoing significant social and economic shifts. By portraying rural life as orderly, balanced, and unchanging, Stubbs captured both the aspirations and underlying tensions of the period. His work offered a comforting pastoral vision that appealed to his patrons, reflecting their desire to see the countryside as a stable refuge amidst broader change.

The Transformation of the British Countryside: Reconsidering George Stubbs’ The Reapers in the Context of Eighteenth-Century Landscape Painting

At first glance, George Stubbs’ The Reapers (1783) may appear to modern viewers as a nostalgic celebration of the British countryside—a peaceful scene of rural labour in harmony with nature. Yet for contemporary audiences in the late eighteenth century, the painting would have carried deeper significance. This period marked a time of profound change, as the landscape was being dramatically reshaped by agricultural reform and early industrial developments.

Works like Stubbs’ and earlier paintings by artists such as Thomas Gainsborough offer more than just picturesque views; they subtly obscure the social and economic upheavals that were transforming rural life. Through these idyllic landscapes, we can trace the early emergence of modern forces—industrialisation, resource exploitation, and environmental change—that left a lasting impact on both people and the land during this era of rapid transformation.

The Enclosure Movement and Transformation of the Countryside

By the time Stubbs painted The Reapers, the British countryside was undergoing profound transformation through the Enclosure Movement—a process that privatised common land and consolidated small farms into large, privately owned estates. This sweeping change upended the agricultural system that had shaped rural life in England for centuries. Land that had once been shared by villagers, offering access to common pastures and essential resources, was now fenced off and divided into orderly plots controlled by wealthy landowners.

Enclosure drastically altered the appearance of the landscape, replacing open communal fields with neatly partitioned areas, often bordered by hedgerows or fences. The land was reorganised for more intensive and specialised agricultural production. While this system increased efficiency and productivity, it came at a great social cost. Many rural labourers lost access to land that had sustained their families for generations, forcing many to migrate to growing urban centres in search of work—foreshadowing the wider shifts of the Industrial Revolution.

In The Reapers, Stubbs portrays a tidy, harmonious vision of rural life: well-dressed labourers harvesting golden fields beneath the watchful eye of a landowner. This image reflects the visible orderliness brought about by enclosure, yet it masks the underlying reality of social upheaval and displacement. Behind the painting’s sense of productivity and calm lies a more complex truth—one where the transformation of the countryside often came at the expense of the very people working the land.

Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews: A Landowner’s Perspective

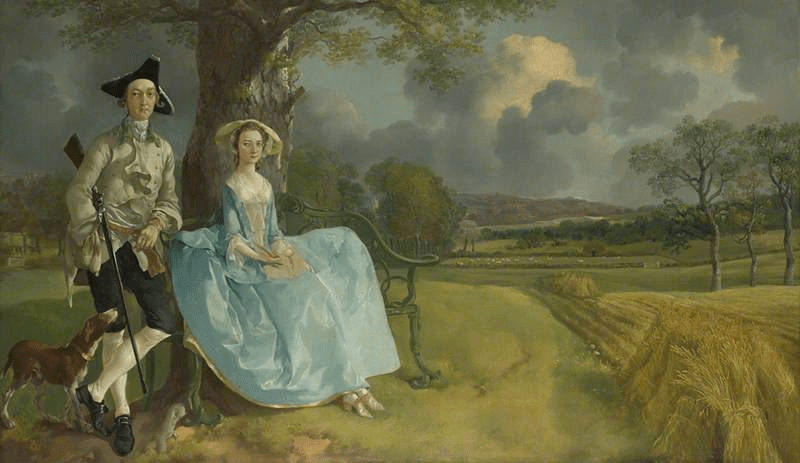

Fig 2: Mr and Mrs Andrews by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), The National Gallery, London.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London. Sourced via Art UK.

As a counterpoint to The Reapers, Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (c.1750) presents another vision of a shifting countryside—this time seen through the eyes of privileged landowners. The double portrait captures a newlywed couple proudly situated on their estate, with the landscape extending beyond them. To the right, fields stretch out in tidy, enclosed sections, a clear reflection of the changes brought about by the Enclosure Acts. These physical boundaries symbolise the increasing dominance and control the landed elite held over newly partitioned land.

Where Mr and Mrs Andrews casts the landscape as an emblem of prosperity and prestige, it also quietly speaks to the reshaping of rural life by human hands. The precise, almost geometric layout of the farmland hints at a new agricultural order: one where land is commodified, concentrated in ownership, and restricted from communal use. For the couple depicted, this transformation affirms their social standing and modern sensibilities. But for those beyond the frame—displaced farmers and rural labourers—it marks the erosion of traditional ways of living, and the loss of access to both land and independence.

Landscape as a Reflection of Industry and Modernisation

Both Stubbs and Gainsborough depict the countryside through an idealised lens—one that romanticises the relationship between landowners and labourers. Yet beneath these tranquil scenes lies subtle traces of a world in transition. The sharply defined fields, orderly crops, and systematically divided land reflect a deeper transformation: the move from a communal, medieval landscape to a structure shaped by capitalist agriculture.

This evolution laid the foundation for modern conceptions of land use, industry, and resource management. Enclosure not only streamlined agriculture and boosted food production for booming urban centres—it also marked a shift in perception. Land became a resource to be organised, owned, and exploited for efficiency. Viewed this way, paintings such as The Reapers become more than mere records of rural life—they offer visual premonitions of the industrial ethos soon to dominate society.

Stubbs’ pastoral portrayal of reapers at work, while suggestive of harmony, also glosses over the sweeping changes already underway in the countryside. Land consolidation, increased agricultural output, and the displacement of rural workers were all integral steps toward industrialisation. The image quietly holds dual meaning: a nostalgic remembrance of agrarian life, and a foreboding glimpse of a future defined by mechanisation, resource extraction, and the reconfiguration of our relationship with nature.

The Legacy of the Enclosure Movement: Industry, Energy, and Pollution

The enclosure of land dramatically reshaped the rural landscape, but its impact extended far beyond the countryside—it played a pivotal role in the rise of industry and the emergence of modern ideas around energy and pollution. As farming techniques became more efficient, displaced rural labourers moved into urban centres, supplying the workforce needed for the factories and mines that powered the Industrial Revolution. In this way, the enclosure movement helped usher in the shift from an agrarian society to an industrial one.

With this transition came a more extractive relationship with the land. Whether through agriculture or mining, the economy became increasingly dependent on the exploitation of natural resources. The tranquil, orderly fields depicted in paintings like The Reapers may appear serene, yet they hint at a new attitude towards nature—one driven by productivity, control, and profit. These managed landscapes foreshadow the environmental consequences to follow: deforestation, soil degradation, and the rise of industrial pollution.

By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, artists responded more directly to the environmental toll of industrialisation. Scenes once filled with pastoral charm began to feature factories, smokestacks, and coal mines. Landscapes that had celebrated harmony and abundance were now altered by the visible scars of extraction—reflecting not only aesthetic change, but the shifting values of a modernising world.

Reassessing the Pastoral Tradition

George Stubbs’ The Reapers and Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews belong to the pastoral tradition in British art—a genre that romanticises rural life and humanity’s bond with nature. On the surface, these works evoke nostalgia for a simpler, agrarian existence. Yet, when placed within the context of historical change, they reveal far more than sentimental charm. They subtly expose the early stirrings of modernisation and the rise of capitalist land management—forces that would reshape not only Britain’s countryside but global landscapes beyond.

A close examination of these paintings uncovers the origins of modern ideas around industry, energy use, and environmental extraction. The serene, structured fields of the 18th century—portrayed as harmonious and fertile—are early indicators of a profound shift. These images foreshadow the movement toward industrialisation, urban expansion, and the ecological pressures that define the contemporary world.

In this light, Stubbs’ and Gainsborough’s works become more than pastoral scenes: they serve as quiet witnesses to a transforming relationship between humans and the land—one that continues to unfold in our own time.

The Birth of the Industrial Revolution: A New World

The Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the late 18th century and gradually spread across the globe throughout the 19th century, marked a pivotal moment in human history. This era of sweeping social, economic, and technological transformation radically changed the way people worked, lived, and understood the world around them. Its influence on art was profound—the period reshaped artistic practices, themes, and the materials available to artists. This article explores how industrialisation redefined the conditions of artistic production and inspired new aesthetic responses.

With the rise of machines, factories, and large-scale mass production, industries such as textiles, transport, and manufacturing underwent revolutionary change. Innovations like the steam engine, spinning jenny, and power loom catalysed unprecedented growth, transforming urban landscapes and giving rise to a new working-class population. As rural communities transitioned from agricultural life, many migrated to rapidly expanding cities in search of factory work. This shift not only altered the fabric of society—it shaped everyday experience, political thinking, and inevitably, artistic expression.

Early Artistic Reactions: Romanticism’s Response

At the dawn of industrialisation, many artists responded with unease to the rapidly shifting landscape around them. The Romantic movement—emerging in the late 18th century and flourishing through the mid-19th—offered a passionate, imaginative counterpoint to the growing mechanisation of society. Poets, writers, and painters within this tradition rejected the stark, impersonal nature of industry, choosing instead to celebrate emotion, individuality, and the beauty of the natural world.

Landscape art became a powerful medium for expressing this resistance. Artists like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable painted vivid portrayals of nature’s grandeur, evoking a sense of awe that stood in stark contrast to the smoke and grime of industrial cities. Their works often depicted the natural world as a vast, sublime force—one capable of overwhelming human invention. Turner’s Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway (1844), for instance, embodies the tension of its time, capturing both the exhilaration of technological advancement and the haunting encroachment on the natural landscape.

Fig 3: Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), 1844, The National Gallery, London, England, UK.

Image featured in an article on the DailyArt Magazine website: Industrial Landscapes.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London.

Fig 4: The White Horse by John Constable (1776–1837), 1819.

The Tate, London.

Image featured on the Tate website.

Realism: Art in the Age of Industrial Labour

By the mid-19th century, as industrialisation became an undeniable force shaping daily life, many artists began to shift away from the Romantic idealisation of nature. Instead, they turned their attention toward the unembellished realities of modern society. This transition gave rise to the Realist movement, led by figures such as Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, who sought to depict the lives of ordinary people with honesty and empathy. Their works often highlighted the hardships of the rural poor and the emerging urban working class, offering a visual commentary on the social conditions brought about by rapid industrial change.

Fig 5: The Stonebreakers (1849), oil on canvas by Gustave Courbet (1819–1877). Originally part of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister collection; destroyed during the bombing of Dresden in 1945.

The Stone Knockers (copy after Gustave Courbet) by L. Schünzel, 1926/27. Oil on canvas, 85 × 121 cm.

Albertinum, Dresden. Inventory no. 89/30. Image featured on the Art Collections Dresden website.

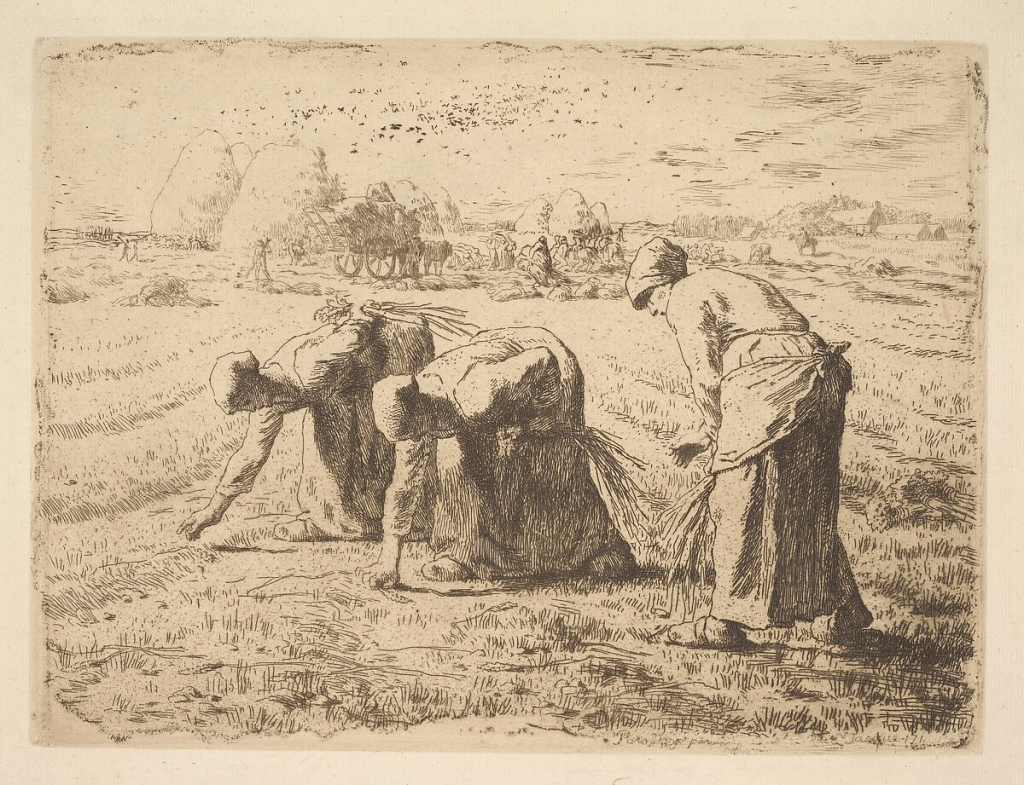

Fig 6: The Gleaners by Jean-François Millet (1814–1875), published by Auguste Delâtre (1822–1907), 1834–75.

Etching printed in brown/black ink on laid paper; second state of two. Image: 18.9 × 25.4 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Image featured on the Met Museum website.

In the work of Realist painters, the overlooked and undervalued—industrial labourers, peasants, and the urban poor—emerged as central subjects. Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849) and Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners (1857) are powerful examples, portraying manual labour not with sentimentality but with sober dignity. These images reflect the growing impact of industrial capitalism, drawing attention to the stark class divisions it intensified. By documenting the struggles of everyday working people, Realist artists underscored the social costs of economic progress and challenged viewers to confront the realities behind modernisation’s rise.

The City as a New Subject: Impressionism and Modernity

As the Industrial Revolution surged forward into the late 19th century, it radically transformed cities like Paris and London into energetic hubs teeming with railways, factories, and rapidly evolving modes of transportation. The modern city—characterised by speed, movement, and the relentless rhythm of urban life—became a compelling subject for Impressionist painters.

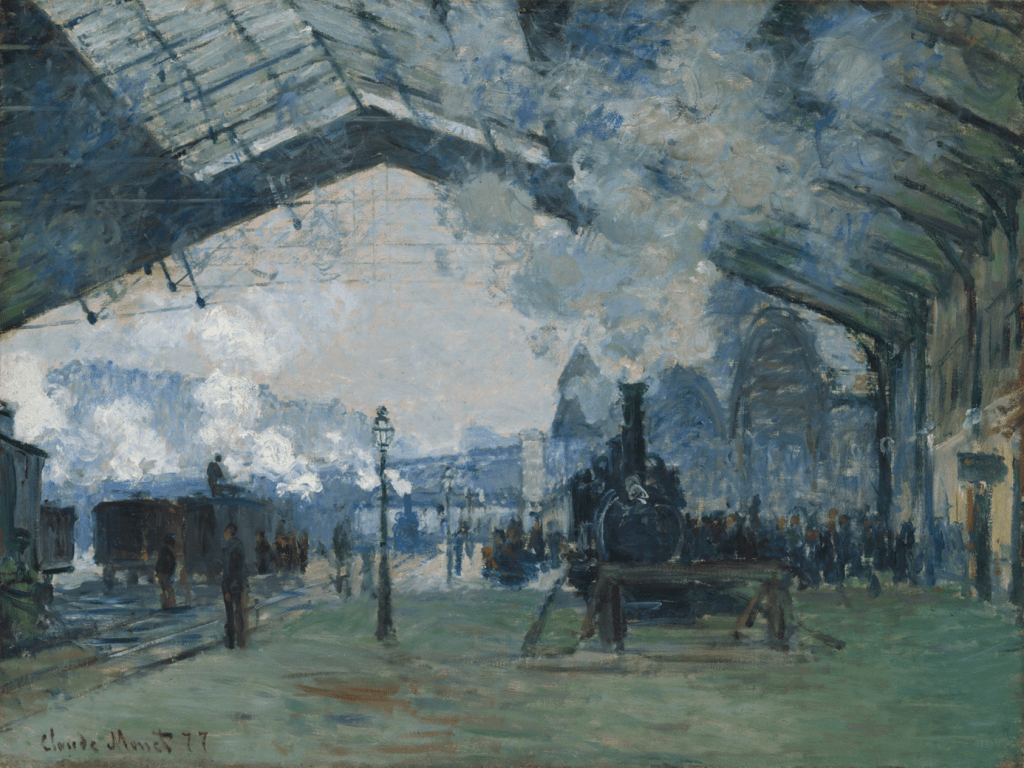

Artists such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro turned their gaze toward these changing landscapes, capturing the vitality of bustling streets, smoky train stations, and industrial architecture. Monet’s La Gare Saint-Lazare series (1877), for example, vividly conveys the sensory experience of urban transit—billowing steam, flickering light, and the flow of passengers weaving through a world of iron and motion. With their loose brushwork and sensitivity to light and colour, the Impressionists developed an aesthetic that mirrored the ephemeral nature of modern life—an artistic response to a world redefined by industrialisation

Fig 7: Arrival of the Normandy Train, Gare Saint-Lazare by Claude Monet (1840–1926), 1877.

Oil on canvas, 60.3 × 80.2 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Credit Line: Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection. Reference No. 1933.1158.

Image featured on the Art Institute of Chicago website.

Fig 8: Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich by Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), 1871.

Oil on canvas, 44.5 × 72.5 cm. The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust).

Image credit: The Courtauld. Featured on the Art UK website.

Fig 9: Woman Ironing by Edgar Degas (1834–1917), begun c. 1876, completed c. 1887.

Oil on canvas, 81.3 × 66 cm. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Accession No. 1972.74.1.

Image featured on the National Gallery of Art website.

The Arts and Crafts Movement: A Rejection of Industrialisation

While some artists welcomed the rise of industrialisation, others fiercely resisted its influence. The Arts and Crafts Movement, which emerged in Britain during the late 19th century, stood as a bold counterpoint to the mechanical age. Reacting to the impersonal nature of mass production and the decline in quality of machine-made goods, leading figures like William Morris and John Ruskin championed a return to traditional craftsmanship and natural materials.

At its heart, the movement embraced the belief that handmade objects possessed greater moral and aesthetic worth than those churned out by machines. It celebrated the individuality of artisans and the integrity of their craft, advocating for designs that were not only functional but also deeply rooted in personal expression and historical tradition.

Fig 10: Wall hanging, designed by William Morris, made by Ada Phoebe Godman, 1877, England. Museum no. T.166-1978. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Fig 11: Zermatt by John Ruskin (1819–1900), 1844.

Watercolour. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Museum No. P.15-1921.

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Featured on the Art Collections page of the V&A website.

William Morris—a visionary designer, writer, and social reformer—dedicated his career to bridging the gap between art and labour. Believing that creativity should enrich everyday life, he sought to produce objects that were both beautiful and practical. Through his influential work in textiles, wallpaper, and furniture, William Morris championed a return to thoughtful, handcrafted design. His philosophy stood in stark contrast to the soullessness of industrial mass production, embodying a broader mission to restore meaning, aesthetic value, and human dignity in an increasingly mechanised world.

The Machine Aesthetic: Futurism and Modernism

By the early 20th century, a wave of artists began to embrace the energy and momentum of the machine age, viewing industrial progress as a powerful emblem of human achievement. Futurism—an audacious avant-garde movement founded in Italy by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti—celebrated technology, velocity, and the mechanised forces of modern warfare. Rejecting tradition, Futurist artists such as Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla sought to express the dynamism of contemporary life, depicting factories, engines, and urban scenes in bold, fragmented compositions that conveyed motion, speed, and mechanical power.

Fig 12: Unique Forms of Continuity in Space by Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916), 1913, cast 1972.

Bronze sculpture, 117.5 × 87.6 × 36.8 cm. Tate, London.

Image featured on the Tate website.

Fig 13: In the Evening, Lying on Her Bed, She Reread the Letter from Her Artilleryman at the Front (Le Soir, couchée dans son lit, elle relisait la lettre de son artilleur au front) by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944), created 1917, published 1919.

Letterpress, 34.9 × 23.2 cm. Publisher: Edizioni Futuriste di “Poesia”, Milan.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of W. Michael Sheehe, 1995. Object No. 1995.511.1.

Image featured on the Met Museum website.

Fig 14: Abstract Speed – The Car has Passed by Giacomo Balla (1871–1958), 1913.

Oil on canvas, 50.2 × 65.4 cm. Tate, London.

Image © DACS, 2025. Featured on the Tate website.

Meanwhile, the Modernist movement actively embraced industrial themes, redefining the role of art and architecture in an age of mechanisation. Architects such as Le Corbusier drew inspiration from the efficiency and clarity of machine design, integrating materials like steel and concrete into buildings that prioritised function over ornament. His vision of homes as “machines for living” exemplified a new aesthetic grounded in practicality and modernity.

Similarly, the Bauhaus—a groundbreaking German school of art, design, and architecture—sought to dissolve the boundaries between art, craft, and technology. It championed a philosophy of design that was functional, visually refined, and compatible with mass production. Bauhaus artists and designers aimed to create works that reflected the spirit of the industrial age while maintaining humanist principles of simplicity, purpose, and unity.

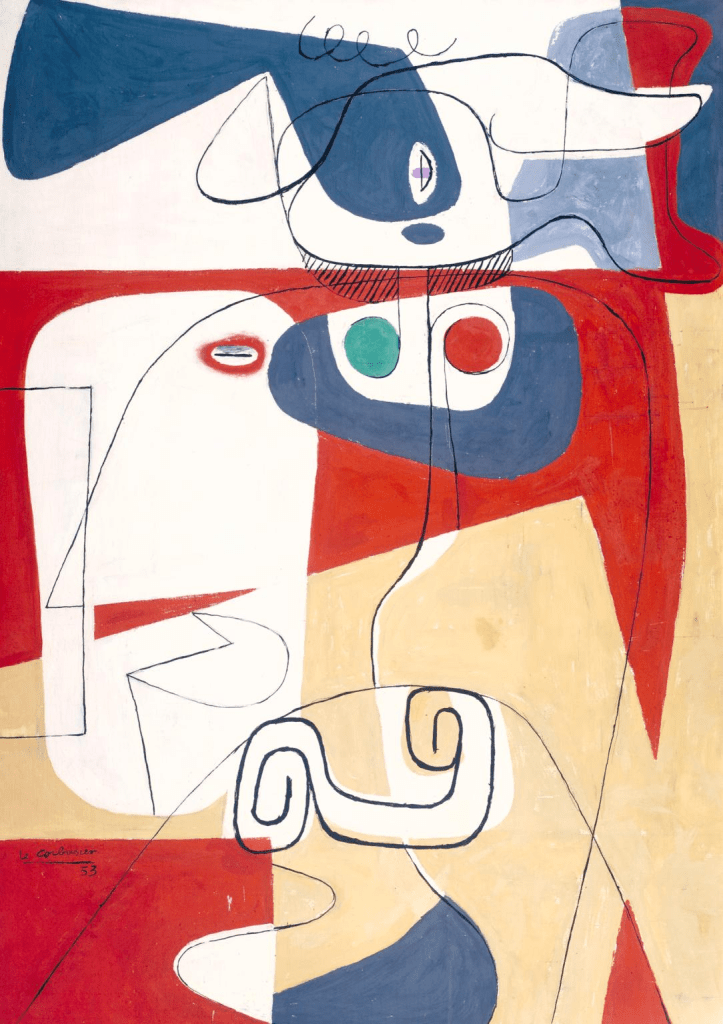

Fig 15: Bull III by Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, 1887–1965), 1953.

Oil on canvas, 161.9 × 113.7 cm. Tate, London.

Image © FLC/ADAGP, Paris & DACS, London 2025. Featured on the Tate website.

Fig 16: Tea Infuser and Strainer by Marianne Brandt (1893–1984), ca. 1924.

Silver and ebony, 8.3 × 10.8 × 16.5 cm.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Credit Line: The Beatrice G. Warren and Leila W. Redstone Fund, 2000. Object No. 2000.63a-c.

Image © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Featured on the Met Museum website.

Photography: A New Art Form of the Industrial Age

The Industrial Revolution not only transformed industry and society—it also revolutionised the very tools of artistic expression. Among the most significant developments was the invention of photography, a medium that emerged directly from the technological innovations of the era. Relying on mechanical processes, photography was both a product of industrialisation and a powerful instrument for reflecting its effects.

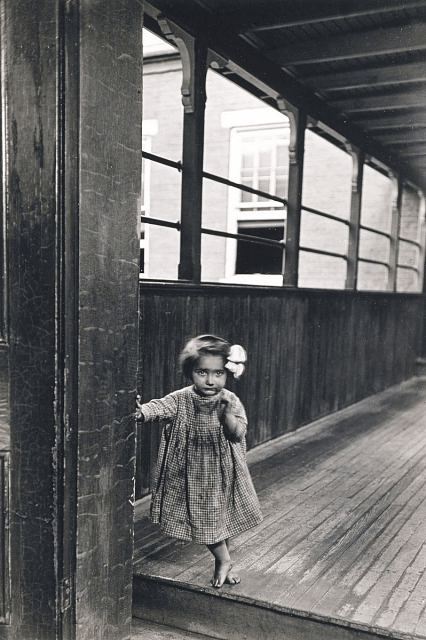

Photographers like Lewis Hine harnessed this new art form to document the realities of modern life with unflinching honesty. His images of factory workers, child labourers, and impoverished urban environments did more than record—they revealed. Through stark compositions and empathetic framing, Lewis Hine’s work exposed the human cost of industrial progress and helped bring social issues into public view, shaping both artistic practice and social reform.

Fig 17: Little Orphan Annie in a Pittsburgh Institution by Lewis W. Hine (1874–1940), ca. 1910, printed later.

Gelatin silver print, 16.5 × 11.5 cm.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. Object No. 1994.91.82.

Image featured on the SAAM website.

Lewis Hine’s compelling photographs—particularly his stark documentation of child labour in American factories—played a pivotal role in advancing social reform. His work revealed the power of photography not only as a vehicle for artistic expression but also as a force for societal change, capable of influencing public opinion and policy

A Complex Relationship

The Industrial Revolution and the evolution of art were deeply intertwined, as industrialisation transformed not only the practical conditions of artistic production but also the themes and styles that artists pursued. From the Romantic resistance to the mechanisation of nature to the Modernist celebration of technology and efficiency, artists engaged with the sweeping changes of their time in varied and often conflicting ways.

This period of upheaval laid a crucial foundation for future artistic movements, prompting generations of creators to explore the shifting dynamics between technology, society, and creative expression. In responding to the industrial age, artists revealed not only its visible impacts but also its emotional and philosophical reverberations—shaping an ongoing conversation between art and modernity that continues to unfold.

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to accurately reference artworks, sources, and image credits based on the information available at the time of writing. If any details have been omitted or misattributed, this is entirely unintentional. I welcome corrections and feedback to improve the accuracy and completeness of future updates.

References:

Websites:

Related Article: Art UK – Art UK main site

Related Article: V&A – Victoria and Albert Museum

Images:

Fig 1: Art UK

Fig 2: Art UK

Fig 3: Daily Art Magazine

Fig: 4 The Tate

Fig 5: State Art Collections Dresden

Fig 6: Met Museum website

Fig 7: Art Institute of Chicago website

Fig 8: Art UK

Fig 9: The National Gallery of Art, Washington

Fig 10: V&A

Fig 11: V&A

Fig 12: The Tate

Fig 13: Met Museum website

Fig 14: The Tate

Fig 15: The Tate

Fig 16: Met Museum website

Fig 17: SAAM website.