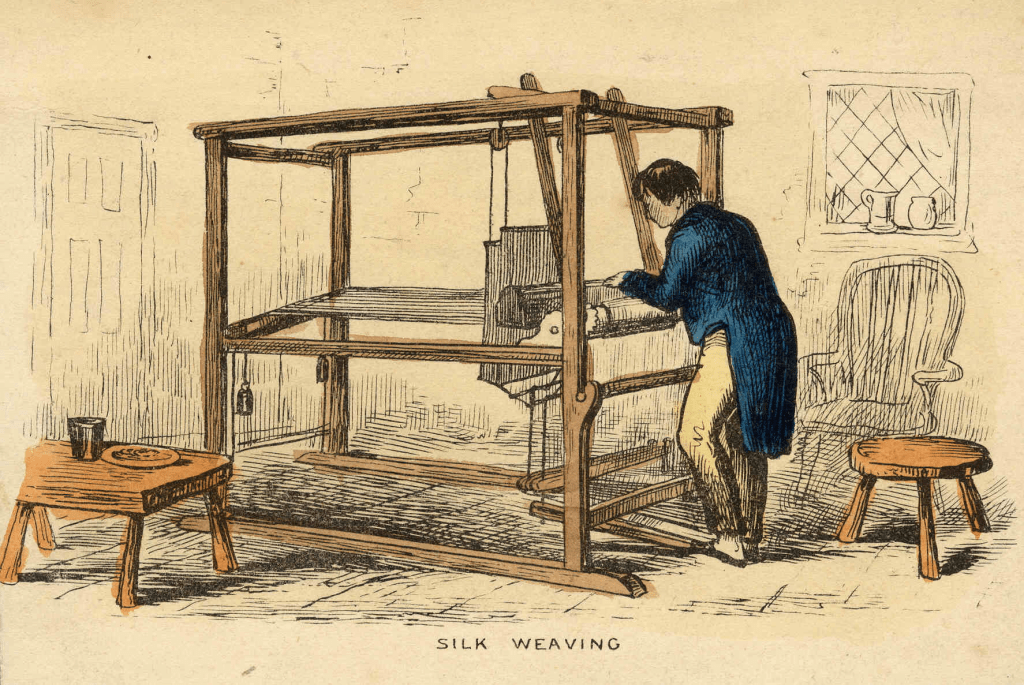

Bristol Radical History Group. (2012). Silk Weaving Image. Retrieved from https://www.brh.org.uk/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/silk-weaving.jpg

As I follow the threads of my family history, one story continues to resonate — that of my grandfather on my mum’s side who worked as a handloom weaver in the days before the Industrial Revolution that transformed Britain’s textile industry. Long before the roar of factory machinery and the rise of industrial mills, weaving was a skilled craft practiced quietly in cottage homes. Known as the cottage industry or domestic system, this method of textile production was central to rural life. Cloth was made one shuttle at a time, with great care and precision, on wooden looms set up in living rooms or small outbuildings.

Living in a rural village, my grandfather belonged to a generation who relied on weaving not only as a livelihood but as a deeply rooted tradition passed down through families. Their craftsmanship supported the household economy and contributed to the broader pre-industrial textile trade — a slow, meticulous process that demanded patience, skill, and rhythm.

But by the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the landscape began to shift. The rise of mechanised mills brought rapid production, cheaper goods, and centralised labour. Rural weavers found themselves increasingly under pressure, unable to compete with factory output. Many lost their means of income, and entire communities were reshaped by the relentless march of industrialisation.

The story of my grandfather offers more than a family connection — it provides a glimpse into a vanished way of life, one where textiles were made by hand, with care, as part of a centuries-old tradition now woven into the fabric of history.

The Role of Rural Weavers

Rural weavers were responsible for turning raw materials such as wool, flax, or cotton into woven fabric and this process involved several stages, where each would often be carried out by different members of a household or community:

Raw Material Preparation:

- The wool was carded and spun into yarn by women and children using spinning wheels.

- Flax required retting, breaking, and spinning to produce linen thread.

Weaving:

- Men, who typically operated the looms, wove the prepared thread into cloth.

- The loom, often set up in a cottage, was a central feature of a weaver’s home.

Finishing:

- Once the fabric was woven, it might be fulled, dyed, or otherwise processed by specialised workers in nearby towns.

Weavers produced a textile for domestic use and would sell it in local markets. However, as the demand for British textiles grew, their output became part of a broader supply chain, particularly in the production of woollen and linen goods destined for export.

Economic and Social Context

What was the Domestic System?

- Rural weavers worked within the “putting-out system,” this was where merchants supplied them with the raw materials and collected the finished cloth.

- This arrangement allowed weavers to work independently while staying close to their families and working on their farms.

Rural Communities

- Weaving was often a family effort, with all family members contributing to this labour-intensive process.

- In many rural areas, weaving supplemented agricultural income, in particular during seasons when farm work was less demanding.

Challenges and Inequalities

- Weavers were subject to fluctuating demand for their products, and this would lead to periods of prosperity and hardship.

- They were dependent on merchants for raw materials and payments, and this unfortunately led to leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

Textiles in Pre-Industrial Britain

Wool: The Backbone of the Industry

- Wool was Britain’s most significant export and was a key material for rural weavers.

- The government heavily regulated wool production and weavers were part of a well-established trade network that connected sheep farmers, spinners, dyers, and merchants.

Linen and Cotton

- Linen was a common textile in rural areas, particularly in Scotland and Ireland, where flax cultivation was widespread.

- Cotton, although less significant than wool before the Industrial Revolution, it began to grow in importance during the 18th century due to trade with India and the Americas.

Life and Work as a Weaver

Daily Routine

- Weavers often worked long hours, particularly during periods of high demand.

- Their work required skill and precision, as mistakes in weaving could ruin a piece of cloth and reduce their earnings.

Tools and Technology

- The handloom was the weaver’s primary tool, and while effective, it was slow compared to later mechanical looms.

- Innovations like the flying shuttle (invented by John Kay in 1733) improved efficiency and allowed the weaver to produce wider fabrics quickly which also increased competition and output expectations.

Community and Culture

- Weaving was deeply embedded in rural life and its culture, where traditions were passed down through generations.

- The rhythm of weaving often matched the seasons, with less time spent at the loom during peak agricultural periods.

The Decline of the Cottage Industry

The Industrial Revolution brought profound changes to the textile industry:

Mechanisation

Machines like the spinning jenny in 1764 created by James Hargreaves allowed one worker to spin multiple spools of yarn simultaneously.

The water frame was created in 1769 by Richard Arkwright and allowed for greater production efficiency by using the power of water.

The power loom was a significant invention during the Industrial Revolution and was created by Edmund Cartwright in 1785. This loom mechanised the weaving process, (as it was previously done manually on handlooms). Here are some key points about the power loom:

Key Features

- Mechanisation: The power loom used mechanical power (initially water, later steam) to automate the weaving process.

- Increased Speed: The power loom significantly increased the speed of the production of cloth compared to handlooms.

- Components: The main components included the warp beam, heddles, harnesses, shuttle, reed, and take-up roll.

- Automation: Over time, the power loom evolved to include automatic features, such as the Northrop loom, which replenished the shuttle automatically.

- Urbanisation: Rural weavers were displaced due to textile production being shifted into industrial towns.

- Competition: Factory-made textiles were cheaper and produced in greater quantities, undercutting the prices that rural weavers could charge.

What was the power loom?

The power loom was a significant invention during the Industrial Revolution, designed by Edmund Cartwright in 1785. It mechanised the weaving process, which was previously done manually on handlooms. Here are some key points about the power loom:

The Impact

- Industrialisation: The power loom played a crucial role in the industrialisation of the textile industry during the Industrial Revolution, leading to the establishment of large-scale textile factories.

- Labour Shift: It reduced the need for skilled handweavers, as the machines could now perform the task more efficiently.

- Economic Growth: The increased efficiency and productivity that the power loom created contributed to economic growth and the expansion of the textile industry.

Legacy of Rural Weavers

Although the Industrial Revolution eclipsed the domestic system, rural weavers left an enduring legacy. Their craftsmanship laid the foundation for Britain’s dominance in textiles, and their traditional craft influenced the design and production techniques of the industrial age. Today, the memory of rural weavers endures in museums, historical re-enactments, and the artisanal weaving communities that continue to celebrate the skill and creativity of this pre-industrial craft.

Rural weavers before the Industrial Revolution epitomised the resourcefulness and resilience of pre-modern communities. While their way of life may have been swept away by industrialisation, their contributions to Britain’s economy and cultural history remain invaluable.

Further Reading:

Axminster Heritage Centre. (2018). Pre-industrial Wool and Weaving. Axminster Heritage.

This PDF offers a beautifully detailed account of Devon’s wool industry before mechanisation, including:

- Early sheep farming and natural wool colours

- Craft-based spinning and weaving methods

- Cottage production and the role of women and children

- The gradual decline of handweaving as industrial mills rose

#RuralWeavers #IndustrialRevolution #Weaving #HandWeavers #Textiles #PowerLoom #WaterFrame #SpinningJenny #CottageIndustry