Original article

by Mark Cartwright

published on 01 March 2023

Textile Industry

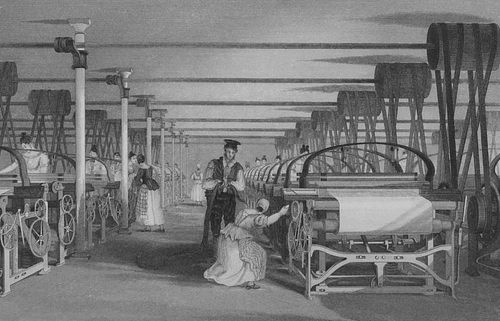

Textile production was once a cottage industry but during the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) it was transformed to a mechanised system. The workers were only needed to make sure the carding spinning, and weaving machines didn’t stop.

There were many inventors who wanted to ensure that the machines became cheaper, faster, and more productive and reliable then ever. This was driven by the desire to cut costs.

This adoption of machines, which typically were powered by water wheels and later by steam engines, would mean that many of the skilled textile workers would lose their employment, and this led to protest movements such as those by the Luddites. Although there were new, and less skilled jobs created, there were poor working conditions in these textile mills, and this helped to form the trade union movement to spur the government to pass laws to protect the well-being of the workers.

The Evolution of the Textile Industry

Before mechanisation it was a tradition that yarn and cloth were purchased from the spinners and weavers working in their own homes or in small workshops. It had become known that families would divide the work, between children who did the washing and then carding the wool, the women would spin the yarn and they used a manual spinning wheel, the men would weave the cloth using a hand-powered loom.

In 1733 production was speeded up when John Kay invented the flying shuttle. It was used to pull thread horizontally (the weft) across longitudinal threads (the warp) on a weaving frame. The shuttle, went across the worked material by a hammer, this method would also permit wider textiles to be made.

A problem arose, which was how can we spin more yarn to keep up the pace with the faster weaving stage? The traditional spinning wheel was an efficient machine but wasn’t effective as it could only spin one thread at a time. This meant that consequently, inventors would attempt to create machines that would spin multiple threads simultaneously, using only one operator to effectively do the work of several people. If there were many machines placed together – inside a factory or mill – production costs could be reduced further. “As in many other areas of the Industrial Revolution, it was the lure of making more money that drove the move away from manual to machine labour.”

Many inventors and machines were created throughout the textile industry during the Industrial Revolution, but the most important include:

- The Spinning Jenny by James Hargreaves (1764)

- The Water Frame by Richard Arkwright (1769)

- The Spinning Mule by Samuel Crompton (1779)

- The Power Loom by Edmund Cartwright (1785)

- The Cotton Gin by Eli Whitney (1794)

- The Roberts’ Loom by Richard Roberts (1822)

- The Self-Acting Mule by Richard Roberts (1825)

- Howe Sewing Machine by Elias Howe (1844)

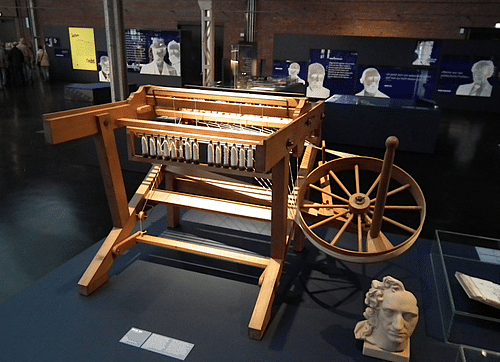

Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny

The spinning jenny (machine) was invented by James Hargreaves (1720-1778) in Lancashire in 1764 (it was patented in 1770). This machine – was a spinning frame that contained multiple spindles – they could spin eight cotton threads at the same time, which meant there was the potential to dramatically speed up production, cutting labour costs and would also attract business owners.

James Hargreaves improved his spinning jenny, which meant a single machine would spin 120 threads simultaneously, and this evolution would more than make up for the higher cost of the new jenny compared to the traditional spinning wheel (70 shillings against one shilling).

By the year 1788, all the factories across Britain would use over 20,000 spinning jennies. This meant, there was no going back to the old cottage industry, where workers would produce textiles in their own homes, this was especially true as many of the machines would use large water wheels for their power.

The traditional textile workers, would immediately see these machines as a threat and smashed any examples they could find, in some cases, they would even burn down factories. Meanwhile, the spinning jenny was introduced to the textile workers of France, it was delivered directly from Lancashire. From 1771, although, it didn’t take off as quickly as it did in the UK, and despite the French-state subsidising their adoption (the reason may be due to their wages being lower in France) these expensive machines were less attractive for entrepreneurs. It could also be true for India, labour was cheaper still and the spinning jenny was largely ignored.

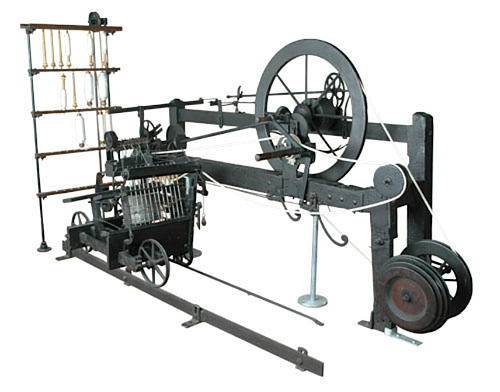

Arkwright’s Water Frame

A Lancashire wigmaker, Richard Arkwright (1732-1792), would create the first water frame. It was a device that was patented in 1769. Richard Arkwright would be crucially assisted by his friend John Kay, who was a clockmaker (not the flying shuttle inventor). Over five years, he helped him perfect the introduction of the right materials to use inside the machine and the gears that made the machine work more efficiently, this machine would replace the more cumbersome system of levers and belts.

As the economic historian R. C. Allen notes, “without watch-makers, the water frame could not have been designed” (204).

At the time, Britain was at the forefront of watchmaking technology, and this again would explain why it was here, not in other countries around the world that the early textile machinery was pioneered. Not coincidentally, but, perhaps, as the heart of the British clock industry was in Lancashire, this was precisely where the mechanised textile industry took off.

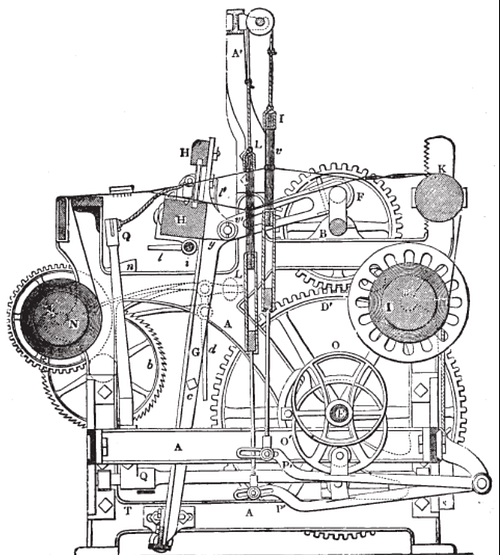

Richard Arkwright’s water frame was a cotton-spinning machine that enabled rollers to perform the task that fingers and thumbs once had. It became an improvement on the spinning jenny, since it produced a much finer and stronger yarn. There was an earlier version that was powered by a single horse and it could spin 96 spindles at once. The fully-developed machine in Richard Arkwright’s factory in Cromford on the River Derwent (far away from any textile workers for his own safety and that of his machines) was powered by a water wheel, it could run indefinitely and more smoothly than hand-worked machines.

The version of Richard Arkwright’s water frame, of 1771 held 129 spindles and it was operated by women. The reason being, was that skilled male textile workers were no longer needed and the factory model of Cromford with its machines and layout, rationalised the production process, the provision of power on multiple floors, and full-time operations would be copied in factories across the north of England.

Richard Arkwright made a fortune by insisting that buyers order no less than 1,000 of his machines at a time (more accurately, the right to build them). This Cromford factory model was copied, in the United States and Germany.

Richard Arkwright greatly improved his wealth by inventing a carding machine (patented in 1775), an invention that would provide a better quality source material for the spinning machines, and the carding machine cut labour costs far more than the water frame.

Crompton’s Spinning Mule

The spinning mule was invented by Samuel Crompton in 1779, and is an improved version of the Hargreaves’ jenny and Arkwright’s water frame that made finer and more uniform yarn. This machine could measure up to 46 metres (150 ft) long and it hugely increased the number of available spindles. The machine could have 1,320 spindles but it was complex and needed three workers to operate it. The spinning mule was a success, and by the 1790s, they became steam-powered. One factory could have 60 of these machines, and very soon there were 50 million mule spindles spinning away in Lancashire.

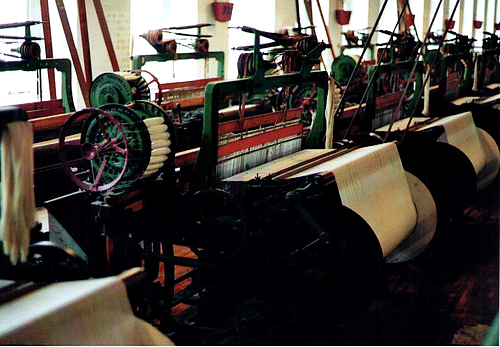

Cartwright’s Power Loom

The power loom weaving machine, was invented by Edmund Cartwright (1743-1823) in 1785.

Edmund Cartwright was a former clergyman. He was inspired to create the water-and then steam-powered loom after he visited a factory in Derbyshire. This fully automated machine would only need a single worker to change the full spindles every seven minutes or so. The power loom machine doubled the speed of producing cloth, but it wasn’t very efficient; there were subsequent inventors who “worked on this problem with success, but Cartwright’s theoretical principles were sound, and he himself never stopped improving his invention.”

The power loom was effectively used first in factories that were owned by Richard Arkwright, but textile factories across the country would soon be equipped with hundreds of power looms.

The UK government awarded Richard Cartwright £10,000 in 1809, which was to thank him “for the significant contribution the power loom made to British industry. In 1821, Cartwright was made a Fellow of the Royal Society.”

Whitney’s Cotton Gin

The methods of the spinners needed to keep up with the weavers, and those who would supply the raw cotton also needed to increase their production to meet the demand.

Eli Whitney (1765-1825) was from Massachusetts, in the USA. He moved to a cotton plantation in Georgia and created an efficient way to separate the sticky seeds from the cotton balls. He invented Whitney’s Cotton Gin (a ‘gin’ meant ‘machine’). It was invented in 1794, it was powered by horses or a water wheel. The machine “pulled raw cotton through a comb mesh where a combination of revolving metal teeth and hooks would separated it and removed the troublesome seeds.”

A single cotton gin processed up to 25 kg (55 lbs) of cotton each day. Just like Crompton and Cartwright, Whitney’s invention became a victim of its own success. Unfortunately he made little money from his machine as it was copied widely and this was despite him registering his machine with the patent office.

As the production of cotton rocketed, more and more slaves were needed on the cotton plantations. They picked the cotton balls that were fed in to the gins. Exports of cotton went far and wide, and in the UK in 1790, cotton accounted for 2.3% of their total imports; and by 1830, the figure rocketed to 55%. British textiles accounted for half of Britain’s total exports by 1830. the cotton textile mills worked the raw material and exported it out again with such success.

THE MACHINES WOULD PUT MANY SKILLED TEXTILE WORKERS OUT OF A JOB, THIS LED TO MANY PROTESTING, VIOLENTLY.

All three branches of the textile industry became mechanised – the raw material production, spinning, and weaving. Better efficiency and greater profits still spurred on the inventors, as textile manufacturing by now was big business. The costs were high to set up a machine factory, roughly £15,000 in 1793 (this would be around $2 million today). As Allen notes, “Cotton was the wonder industry of the Industrial Revolution” (182).

Roberts’ Loom

Richard Roberts (1789-1864) invented the very first cast-iron loom, which was powered by steam in 1822. Using iron instead of wood (as in Cartwright’s loom) would mean that the machine would not warp, therefore the tension of the yarn was kept constant. This would mean that there were now much fewer instances of the yarn snapping or becoming so loose it got tangled in the machinery, and meant production of woven cloth was now faster than ever.

Inventors kept on improving their machines, in Britain and in other countries, and by the 1790s, the British government had prohibited exports of machinery, this was to safeguard its competitive advantage, however, machines did get smuggled out of the country and were used to set up mills in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. These machines were now more efficient than ever, meaning “that, despite the capital outlay required to acquire them, they became profitable even in places with much lower labour costs than in Britain.”

Calico (a cheap cotton material) printing machines of the 1780s, enabled patterned textiles to be made, this was done by using pre-punched cards.

A Frenchman called Joseph-Marie Jacquard (1752-1834) invented a machine that created patterned silk fabric, around 1800, also using pre-cut cards. This Jacquard loom was adopted almost everywhere that textiles were made.

Roberts’ Self-Acting Mule

Richard Roberts continued working on his mechanised looms, and came up with something new in 1825. Richard Roberts had a spirit that was creative and driven by self-interest. Weaving had leapt forward and this was with thanks to his loom but spinning couldn’t keep up with supply and the yarns the weavers needed. This in turn would limit sales of the Roberts Loom.

Richard Roberts invented a spinning machine that ran with very little input from workers, this meant they could run around the clock. These machines used gears, cranks, and a guide mechanism that ensured the yarn would always be placed exactly where it needed to be, the spindles turned at varying speeds, which depended on how full they were (hence the machine’s ‘self-acting’ name).

Richard Roberts’ loom and mule combined would provide the mill owners with exactly what they wanted: “a factory floor with as few humans in it as possible.”

Around 75% of cotton mills by 1835 were steam powered, there were also well over 50,000 power looms being used in the UK.

A steam-powered factory didn’t need to be near a water source, and this meant that better sites could be chosen that were close to natural resources like coal. As the machines became “ever more versatile, cheaper, efficient, and reliable machines, the textile industry had become almost completely automated, certainly to the extent that machine operators no longer needed any textile skills.” This meant that skilled workers “would lose their jobs to semi-skilled labourers, but there were more of the latter than the former thanks to the growth in the textile industry.”

As Britain’s textile industry became mechanized this meant that they could “now better its main rival India in production, and so exports boomed. Labour in India was cheap, but the British machines were faster, producing in 2,000 hours what an Indian ‘factory’ needed 50,000 hours to achieve. In short, the British “cotton mill of 1836 was so efficient that it could out-compete hand spinning anywhere in the world” (Allen, 187).

Howe’s Sewing Machine

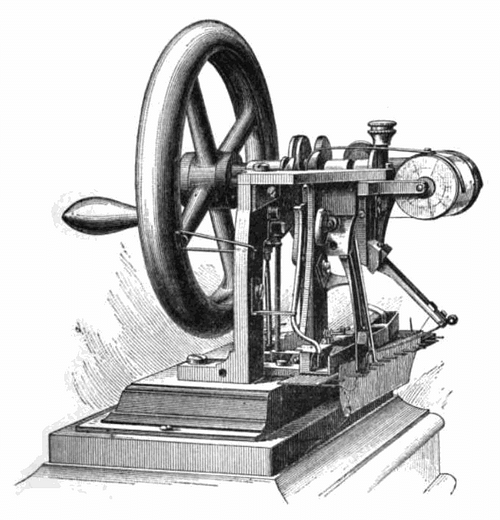

In Cambridge, in the United States Elias Howe (1819-1867) invented a new type of sewing machine in 1844 (patented in 1846). This machine used the lockstitch (where there are two threads put in the cloth, one from below and one from above). Textiles were much stronger using the lockstitch even if the sewing thread broke, and the whole line of stitches didn’t unravel. This new machine was quicker than someone sewing by hand – in fact 640 stitches per minute, compared to an average of 23 by hand. This meant “a calico dress took around six and a half hours to make by hand but just under an hour by machine. The clothing industry was completely revolutionised” (Forty, 149).

Imitation companies popped up, and notably one company owned by Isaac Merritt Singer, he was “obliged to pay royalties to Howe and give him a share in I. M. Singer and Co., a company which went on to become one of the leading sewing machine manufacturers, selling some half a million machines each year by 1870.”

Howe would keep on “developing his idea, making smaller machines and adding a power source from a foot pedal, which meant that the textile industry went full circle, and once again, people had the opportunity to produce clothes and other textiles in their own homes.”

Consequences: The Luddites

The introduction of machines in the textile industry meant that “textile products were cheaper to buy for everyone, and supply industries like the cotton plantations and coal mines boomed. The increase in the number of factories meant many new jobs were created, albeit largely unskilled work. The populations of cities and towns like Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, and Halifax increased ten times over in the 19th century as people in the countryside flocked to cramped and unsanitary urban centres to find work.”

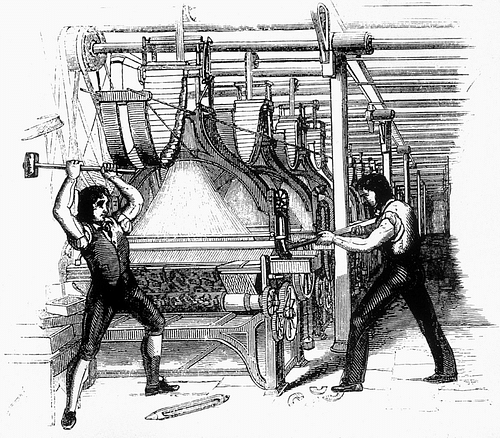

When machines arrived they put a lot of skilled textile workers out of a job, this meant that many of these workers would protest violently against the loss of their livelihood and/or the reduction in their wages. This would mean that “great manufacturing cities of Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Nottinghamshire between 1811 and 1816, a new protest group emerged, the Luddites, named after their mythical leader Ned Ludd, aka King Ludd.” Luddites broke into the factories and smashed the machines, which had taken away their jobs. “The Establishment fought back. Handsome cash rewards were offered for information on or for the capture of Luddites, and the army was called in to protect factories and their owners. Those protestors who were caught faced harsh penalties that included hanging or deportation to Australia.”

Working Conditions & Trade Unions

Difficult working conditions in textile mills were experienced by the workers, machines were noisy and sometimes dangerous when they failed to work “falling heavy parts and shuttles flying out like missiles with alarming regularity”, the atmosphere in the factories needed to be kept warm and damp, this would keep the cotton thread supple and strong. These conditions meant that many of the workers suffered a variety of health problems, in particular with their lungs.

The working day was usually 12 hours in a factory and this included night work as the factories and their machines would work around the clock. Women and children were preferred by many employers as they were cheaper. Children would be employed, because they could crawl underneath the machines to pick up cotton waste and stop hanging threads that would clog up the machinery, this was often a lethal task.

Money and efficiency were an obsession of many of the mill owners, their workers would be pressured to work faster and not cause any delays in production. Fines were introduced for workers who had “dirty hands or those who took too long on a toilet break.”

With all these negatives this meant that the workers would eventually group together and protect their interests. Very soon, trade unions were formed to curb the greater abuses, from their unscrupulous employers. The unions would collect funds which helped workers, who became ill or injured and so unable to work or be paid. The mill owners didn’t like limits on their profits, the government banned trade unions between 1799 and 1824, but the unions who protected workers could not be stopped indefinitely.

There were several acts of Parliament which were passed from 1833 and some not always successfully, to limit the workers employers’ exploitation and lay down minimum standards. There were also new regulations that included the minimum age children could work, and the length of shifts, to prohibit night work for women and children, and the obligation that owners would build protective screens for their more dangerous machines, and to appoint government inspectors.

Textiles factories offered valuable employment, to its workers but the factories remained noisy, dangerous, and unhealthy places for their workers.

“The poet William Blake’s 1808 description of factories as “dark satanic mills” (Horn, 52), sadly, remained apt long after the Industrial Revolution had passed.”

Bibliography

- Allen, Robert C. The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective . Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Armstrong, Benjamin. Britain 1783-1885 . Hodder Education, 2020.

- Dugan, Sally & Dugan, David. The Day the World Took Off. Channel 4 Book, 2023.

- Forty, Simon. 100 Innovations of the Industrial Revolution. Haynes Publishing UK, 2019.

- Hepplewhite, Peter. All About. Wayland, 2016.

- Horn, Jeff. The Industrial Revolution. ABC-CLIO, 2016.

- Shelley et al. Industrialisation and Social Change in Britain . PEARSON SCHOOLS, 1970.

- Yorke, Stan. The Industrial Revolution Explained& Massive Wheels. Countryside Books, 2005.

World History Encyclopedia is an Amazon Associate and earns a commission on qualifying book purchases.

Online Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2183/the-textile-industry-in-the-british-industrial-rev/